Welcome remarks by Jayant Prasad, DG IDSA

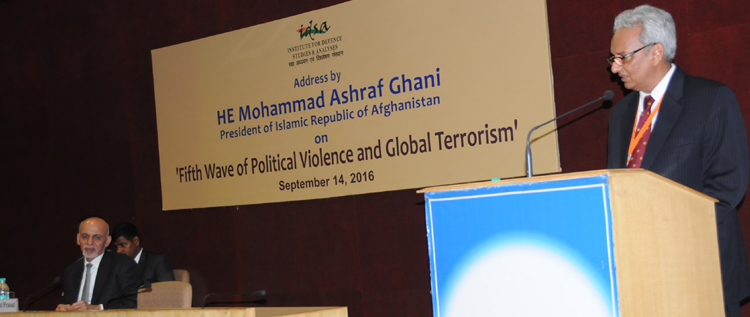

Welcome remarks by Jayant Prasad, DG IDSA at the Special Address by President Mohammad Ashraf Ghani ‘Fifth Wave of Political Violence & Global Terrorism’, September 14, 2016

Hon’ble President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, His Excellency Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, His Excellencies Mr. Salahuddin Rabbani, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Mohammad Hanif Atmar, National Security Advisor to the President – many present here will recall he had spoken at the IDSA in January this year – Mr. Ekil Ahmed Akimi, Minister of Finance, Mr. Sattar Murad, Minister of Economy, Dr. Mohammadullah Batash, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation, Dr. Shaida Mohammad Abdali, Afghanistan’s Ambassador to India, Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen.

It is my honour to welcome the President of Afghanistan and the distinguished team accompanying him to the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. We appreciate the presence of the many Afghan dignitaries with us this afternoon.

The leaders of both India and Afghanistan are committed to a deep and wide development partnership between our two countries that have the closest cultural consonance. Our peoples maintain fraternal ties.

It is hard for anyone to introduce a person as unique and well-known as President Ghani.

He is a statesman, now guiding the destiny of a state whose future will shape peace and stability in the region and the world. His adult life before 2001, for almost a quarter century, was spent in institutions preparing for his present challenges.

As an anthropologist trained in Colombia University, he has helped in refocusing the work of the World Bank towards public education, health, livelihood, and social security, and towards the eradication of poverty, supplementing infrastructure building, which was the World Bank’s original vocation. That work brought him to China, Russia, and India, a country that he knows well.

As an educationist, he has taught in several institutions, perhaps for the longest period in Johns Hopkins University. For several years, he was Chancellor of Kabul University. In 2009, together with Clare Lockhart, he published an acclaimed book, Fixing Failed States: A Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World.

Following his experience as Finance Minister, when he contributed to building the Afghan public finances – its central bank, budgeting and auditing procedures, taxation and customs systems, and the emblematic National Solidarity Programme, in which he partnered with Mr. Haneef Atmar, who was then the Minister of Rural Development, President Ghani is now engaged in the project of state building, in circumstances that are far from ideal.

President Ghani is rebuilding a state system, wracked by over three and a half decades of unrelenting violence. Institution building, governance, economic development and the provision of public goods is compromised by resurgent violence and a relative decline in international engagement.

He believes – in his own words – that the greatest tragedy for Afghans is that Afghanistan is potentially one of the richest countries in the region, and yet is inhabited by extraordinarily poor people. Afghanistan can only be sustained if it becomes, as it has been through much of its history, the crossroads or roundabout between Iran, Central Asia and the Gulf on the one hand and India and China on the other hand. Afghanistan’s future will be secure when it is allowed to become a trade, transportation, energy, and minerals hub for our region.

President Ghani first spoke of the ‘Fifth wave of political violence’, in his seminal speech at this year’s Munich Security Conference. Indeed, he coined this term, and has intellectual ownership of it, having further enlarged on its ramifications at RUSI in London and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation meeting in Tashkent, successively in May and June this year.

According to President Ghani’s account at Munich, the fifth wave of violence, constituted by the post-9/11 terrorism, was preceded by anarchism, national self-determination, new left struggles in Japan, Europe, and the United States, and the ‘Jihad’ against the former Soviet Union in Afghanistan and the struggle in Sri Lanka.

On the predicament of his nation, President Ghani mentioned that nearby countries have been exporting their misfits to Afghanistan. He spoke of the threat of networks – of a renewed Al Qaeda, the Tehrik-e-Taliban of Pakistan, the Haqqani Network and the common platform provided to them by the criminal economy.

He then spoke of the additional problems of “state sponsorship of malign non-state actors,” and worse, “how some states behave like non-state actors.” And in Tashkent, he referred to Pakistan maintaining “their dangerous distinction between good and bad terrorists.”

While post-9/11 terrorism has generic markers, the specific nature of the terrorist threats faced by India and Afghanistan are congruent in many ways, since their origins have common elements. National efforts to combat terrorist ideology and groups are important, but their success will always be compromised if support, sustenance, and sanctuary to these groups are available in the contiguity.

For counter-terrorist efforts to succeed against the present or future avatars of terrorism, the denial of safe-havens must go hand-in-hand with the dismantling of the infrastructure of terrorism.

President Ghani is eloquent – in his inimitable style – about what he describes as “the ecology, morphology, and pathology” of this fifth phase of violence. We are awaiting a further elaboration of these themes today.

I have the pleasure, ladies and gentlemen, to now invite President Ghani to deliver his address.