ASEAN-India: Challenges in Economic Partnership

- February 01, 2018 |

- IDSA Comments

At the India-Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Pravasi Bhartiya Divas in Singapore on January 6-7, 2018, the Foreign Minister of Singapore Vivian Balakrishnan emphasised on the need to ‘build more bridges’ between the two sides.1 India’s stupendous diplomatic gesture of inviting all the ten ASEAN heads of state as guests of honour at the Republic Day festivities on January 26 and their participation in the Commemorative Summit that celebrated 25 years of partnership between India and ASEAN on January 25, was precisely a step in that direction.

The journey of India as a dialogue partner of ASEAN started in early 1990s with the initiation of Look East Policy (LEP). In the following years, the geographic ambit of LEP expanded from Southeast Asia to include the Oceania as well as East Asia, encompassing a significant part of the Indo-Pacific. The renaming of LEP as Act East Policy (AEP) in 2014 reflected this reality. The new coinage signalled India’s interest in playing a significant role in the Indo-Pacific region. Further, by choosing an ASEAN Summit at Nay Pyi Taw as the venue for declaring this change, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made it obvious that India will not forget the central role of ASEAN in India’s approach towards the Indo-Pacific.

Economic partnerships play a significant role in India-ASEAN relations and in India’s efforts to reach out to the Indo-Pacific region. The region has witnessed the formation of mega-trade blocs like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Cooperation (RCEP). In the above context, the commentary seeks to place in perspective critical factors hindering the further growth of ASEAN-India partnership, specifically in the economic arena.

The ASEAN Economy

ASEAN is an inevitable partner for India if it has to become a major Indo-Pacific power. The Asian Development Outlook 2017 has projected that Southeast Asia is expected to achieve 5 per cent growth in 2017-18.2 ASEAN is a recognised production base, with most of its members witnessing upward growth for the last couple of years. Domestic consumption and private investments have become the principal factors in ASEAN’s economic development.3 Asian Development Bank (ADB) also estimates that ASEAN Five (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam) will witness remarkable growth in their export trade.

India’s position in ASEAN’s external trade and investment flows has not yet experienced any special momentum. In its external trade, ASEAN’s major partners are China, European Union and the US. On the other hand, in Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), EU, Japan, the US and China are the principal sources of investment inflows. (For details, see Table 1). One interesting fact about ASEAN is that, presently, intra-ASEAN trade contributes almost 23 per cent of its total external trade and intra-ASEAN FDI constitutes approximately 25 per cent of the grouping’s total receipt of FDI.

(Values in billions of dollars and percentage)

|

Sl No. |

Source Country | Cumulative FDI Inflows | Share of Total FDI Inflows |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Japan | 101.4 | 12.9 |

| 2 | US | 100.6 | 12.8 |

| 3 | Netherlands | 51.6 | 6.6 |

| 4 | China | 47.0 | 6.0 |

| 5 | Hong Kong (China) | 40.6 | 5.2 |

| 6 | Luxembourg | 32.6 | 4.2 |

| 7 | Republic of Korea | 27.9 | 3.6 |

| 8 | UK | 25.6 | 3.3 |

| 9 | Australia | 21.7 | 2.8 |

| 10 | Taiwan | 14.7 | 1.9 |

| 11 | India | 14.4 | 1.8 |

| 12 | Ireland | 11.0 | 1.4 |

Source: ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN FDI database4

Facts Pertaining to ASEAN-India Economic Partnership

India contributed only 1.8 per cent of total FDI inflows to ASEAN between 2010 and 2016 (Table 1) and 2.6 per cent in ASEAN’s total external trade.5 Indian investments in ASEAN are heavily concentrated in Singapore. India’s stock of outward FDI in ASEAN is dominated by the service sector (worth of $12,518.4 million between 2012 and 2016), as mentioned in the ASEAN Investment Report.6 The agricultural, fisheries and forestry sector received $25.8 million in the same time period, mining and quarrying $2.7 million, and manufacturing $98.6 million.7

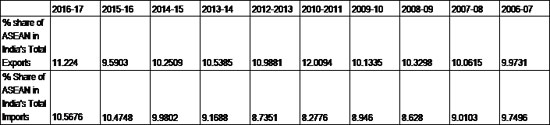

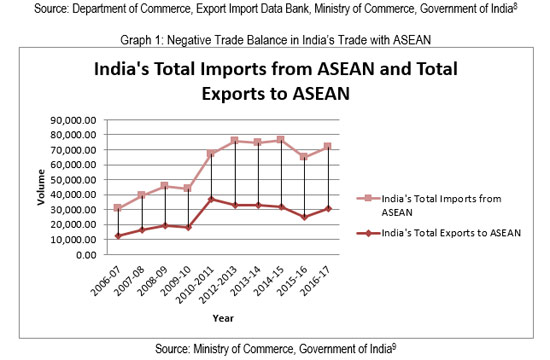

On the other hand, ASEAN as a group contributed almost 16 per cent of total FDI flows to India between 2010 and 2016. From 2006-07 to 2016-17, ASEAN’s share in India’s total exports and imports have risen from 9.97 per cent to 11.22 per cent and from 9.74 per cent to 10.56 per cent respectively. (See Table 2). Notably, the two-way trade between India and ASEAN is tilted towards ASEAN with the trade gap expanding rapidly. (See Graph 1).

Source: Department of Commerce, Export Import Data Bank, Ministry of Commerce, Government of India8

Source: Ministry of Commerce, Government of India9

From Graph 1, it is evident that despite having a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in goods (being implemented since 2010) and trade in services and investment agreement (signed in 2015), India is not benefitting much from its economic cooperation with ASEAN. Though there has been a steady growth in the total trade between India and ASEAN in the last few decades, India suffers from tariff reductions in imports from ASEAN. In value-added sectors including chemicals and applied products, plastics and rubber, minerals, leather, textiles, gems and jewellery, metals, vehicles, and medical instruments, India’s negative trade balance has been increasing.10 The fact remains that the sectors which are suffering from negative trade balance constitute almost 75 per cent of India’s exports to ASEAN.11

Economic Integration: Problems in RCEP and ASEAN’s Doubts over India

On the other hand, ASEAN benefits from economic integration process as already seen from intra-ASEAN trade and intra-ASEAN FDI’s contribution to the region’s economy. In the opinion of ASEAN’s former Secretary General, Le Luong Minh, ASEAN relies on ‘outward-looking approach’, which, it believes, will help in the ASEAN Community building exercise.12 Hence, ASEAN strongly promotes the RCEP which is viewed by it as a next step towards larger integration with six of its FTA partners.13

But India is worried that RCEP will increase its already vast negative trade balance with China (which stands at $50 billion at present)14 and cheap Chinese products will flood the Indian market. This may worsen India’s negative trade balance with ASEAN as well. India’s domestic entrepreneurs, especially those in pharmaceuticals, textiles, dairy and wheat products etc., will suffer, as they may not be able to face the competition from other member countries like Japan, Australia and New Zealand. Lastly, India is unhappy with the restrictions RCEP member countries are putting in place in all modes of services, which include movement of professionals.15

At the 3rd RCEP Ministerial Meetingin May 2017 in Hanoi, India’s then Commerce and Industry Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman pointed out that ‘temporary movement of professionals for activities like installation, trouble shooting, training, maintenance, investment management etc.’ are different from immigration’ and free movement of professionals working in those areas is essential.16 In brief, India wants to ensure liberalisation in services in the RCEP mega-trade bloc; however, RCEP members are not keen on it.

The other problem area relates to India’s preferred three-tier approach as regards tariff reductions on imports, which was rejected by ASEAN and other RCEP members.17 ASEAN’s enthusiasm on RCEP was again reiterated by the Indonesian Trade Minister, Enggartiasto Lukita, who noted that India needs to work with ASEAN to conclude RCEP by 2018.18 This was at the ASEAN-India Business and Investment meeting, held in New Delhi on January 22, 2018. The same was reiterated by the Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the Commemorative Summit, held on January 25, 2018 as well.

Conclusion

The above paragraphs have focussed on some aspects of ASEAN-India economic partnership. First, ASEAN’s share in India’s foreign trade and inflows of FDI is higher than India’s share in ASEAN’s total external trade and FDI inflows. Second, the two-way trade between ASEAN and India is increasing steadily; however, it is in favour of ASEAN and the trade gap is broadening regularly. Third, India’s benefits from the FTA with ASEAN remain nominal.

Despite these challenges in the economic partnership, India’s commitments towards ASEAN have never been compromised. India is committed to assist the CLMV countries (Cambodia, Laos PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam) in their economic development. Connectivity has become the key word in ASEAN-India cooperation. ASEAN and India have expressed their willingness to enhance intra-regional tourism and people-to-people connectivity and civilisational and cultural influences have been reiterated by both sides.

Furthermore, the ASEAN region wants a strong Indian presence as a counter-balance to the growing Chinese influence. This has become evident as India’s defence and security partnership with countries like Vietnam has experienced several positive developments in the recent years. Reciprocity and mutual understanding on common concerns will help both ASEAN and India to overcome some of the challenges facing their relationship.

- 1. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, ‘Transcript of Keynote Address By Minister for Foreign Affairs Dr Vivian Balakrishnan at the ASEAN-India Pravasi Bharatiya Divas Opening Plenary, Sunday, January 7, 2018, Marina Bay Sand’, at https://www.mfa.gov.sg/content/mfa/media_centre/press_room/pr/2017/201712/Press_20180107.html, accessed on January 23, 2018.

- 2. Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook, 2017, p.6.

- 3. Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook, 2017 at https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/365701/ado2017-updat…, as cited in ASEAN Economic Integration Brief, No 2, November 2017, ASEAN secretariat, at http://asean.org/storage/2017/11/AEIB_2nd-edition.pdf, accessed on January 18, 2018.

- 4. ASEAN, ASEAN Investment Report 2017, ASEAN@50 Special Edition, ASEAN Secretariat and UNCTAD, Jakarta, p. 75.

- 5. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, See Note 1.

- 6. ASEAN, ASEAN Investment Report 2017, See Note 4.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. Data for various years collected from Department of Commerce, Export Import Data Bank, Ministry of Commerce, Government of India, at http://commerce.nic.in/eidb/ergnq.asp, data collected and compiled on January 11, 2018.

- 9. Ibid

- 10. Prachi Priya, ‘Regional Comprehensive Economic partnership (RCEP): India Pushes for Greater market Access, ASEAN Irked’, Financial Express, December 6, 2017, at http://www.financialexpress.com/economy/regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep-india-pushes-for-greater-market-access-asean-irked/962428/, accessed on January 22, 2018.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Le Luong Minh, ‘In Pursuit of Regional Economic Integration: The ASEAN Experience’, in ASEAN Economic Integration Brief, See Note 3. No 2, November 2017, ASEAN secretariat, at http://asean.org/storage/2017/11/AEIB_2nd-edition.pdf, accessed on January 18, 2018.

- 13. In RCEP, apart from 10 ASEAN countries, six of its FTA partners, namely, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and India, are involved.

- 14. Amiti Sen, ‘Time for India to exit RCEP trade pact’, The Hindu Business Line, September 7, 2017, at http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/time-for-india-to-exit-rcep-trade-pact/article9850329.ece, accessed on January 18, 2018.

- 15. Press Information Bureau, ‘3rd RCEP Inter-Sessional Ministerial Meeting’, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, May 23, 2017, at pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=162057, accessed on January 15, 2018; Global Times, ‘China Could Work on RCEP Deal without India’, May 4, 2017, at http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1045423.shtml, accessed on January 15, 2018; Amiti Sen, See Note 15.

- 16. Press Information Bureau, See Note 15.

- 17. New Delhi wanted to eliminate tariffs on a three-tier structure which had lesser tariff elimination for China, New Zealand and Australia; moderate for South Korea and Japan and almost 80 per cent for ASEAN.

- 18. The Hindu Business Line, ‘ASEAN pushes India to conclude RCEP this year’, January 22, 2018, at http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/policy/asean-pushes-india-to-conclude-rcep-this-year/article10046655.ece, accessed on January 23, 2018.