China’s Second Coast: Implications for Northeast India

- June 19, 2014 |

- IDSA Comments

Northeast of India has been in the news recently with the coming to power of the new NDA government at the Centre. With the appointment of Gen (Retd) V. K. Singh, former Chief of Army Staff, and now a federal minister of Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (DoNER), the arresting signs are that India is serious about both development and security in this strategic region, bordering Bangladesh, Bhutan, China and Myanmar. Tensions along the China-India border in Arunachal Pradesh compounded by China’s territorial claim, cross-border crime in the India-Bangladesh and Indo-Myanmar borders and the presence of non-state armed actors with bases across the international border vindicates the critical need to mainstream the Northeastern imagination. What is, however, interesting, and of strategic significance, besides China’s growing military presence in Tibet, is its activities in Myanmar especially with regard to ambitions for better access to the sea via the Myanmar coast. China has been assiduously building up its ‘second coast’ in Myanmar overlooking the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. While this build up has the undivided attention of India’s Navy and defense establishment, it would be vital to add the future implications for the Northeast, to make a holistic strategic and security assessment.

China in the Indian Ocean Region

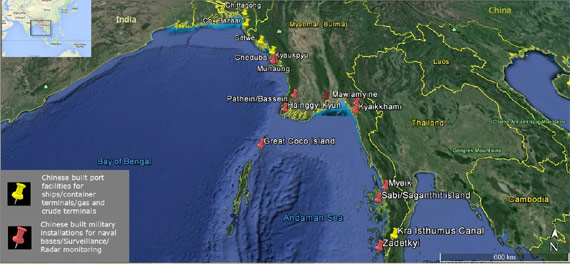

A report by Future Directions International, Australia speculates that China’s overarching strategy for the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) includes constructing military bases and support facilities on foreign soil in proximity to its trade and energy shipping sea lanes of communication (SLOC).1 These areas also called “String of Pearls” in the IOR originate from Hainan Island in the South China Sea, Sittwe in Myanmar, Chittagong in Bangladesh, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Marao in the Maldives, Gwadar in Pakistan, stretching to Kenya and Sudan in the horn of Africa. The strategy includes a canal through the Kra isthmus in Thailand bypassing the Malacca Strait. While these “Pearls” provide the logistics for trade in the SLOCs, it is the Chinese moves to militarily secure both the “pearls” and the SLOCs that have interesting side-effects: capabilities of monitoring Indian Naval activity and the potential to encircle India militarily in the IOR.2

Figure 1 – Overview of the Indian Ocean region

Source: Namrata Goswami

The ‘Second Coast’ and its implications for Northeast India

Myanmar’s 2,276 km long coastline in the Bay of Bengal has the potential to provide the ‘second coast’ to China to reach the Indian Ocean and achieve strategic presence in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Especially transportation logistics to the ‘second coast’ from landlocked south west Chinese provinces like Yunnan have both economic and strategic benefits.

There have been reports of Chinese built SIGINT listening stations in the Andaman Sea at least at Manaung, Hainggyi, Zadetkyi and the Coco Islands in Myanmar. Chinese technicians and instructors have worked on radar installations in naval bases and facilities near Yangon, Moulmein and Mergui. The Indian Coast Guard has intercepted fishing trawlers flying Myanmar flags off the Andaman Islands. On inspection all the crew turned out to be Chinese nationals on expeditions with radio and depth sounding equipment for submarine usage. To what extent these activities and facilities support the Chinese military in monitoring the maritime region around the Andaman &Nicobar Tri command is not yet confirmed.3 Additional reports indicate that the Chinese maybe pushing Myanmar for a listening facility on Ramree Island, Rakhine state, which also holds the deep sea Kyaukpyu port developed for oil and gas transportation. China is building an integrated transport system linking the Kyaukpyu port to Yunnan Province in South West China with the sole aim of reducing energy shipping through the Malacca Strait and South China Sea. The plans include a railroad project from Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, to Kyaukpyu to complete the logistics loop to the ‘second coast’. In 2010, Chinese warships on anti-piracy operations in the Indian Ocean made their first port call to Myanmar.4 China has discussed with President Thein Sein for the PLA Navy’s access to Myanmar’s territorial waters while patrolling the Indian Ocean specifically to provide naval escort and protection to its energy shipments and port facilities at Kyaukpyu in the Bay of Bengal.

Figure 2 – The ‘Second Coast’ of China

Source: Namrata Goswami

Further north from Kyaukpyu port is the capital Sittwe of Rakhine state where China has assisted the Myanmar Navy built a naval base. Interestingly, India’s northeast serving Kaladan River Multi modal transport system feeds off the Sittwe port being developed by India, being the closest to the Kolkata port. As per Indian Navy’s assessment, China’s control of Myanmar’s ports from Sittwe in the north to Cheduba, Bassein and a string of other military assets on the ‘second coast’ can enable it to enforce anti-access/area denial to deny the Indian Navy the ability to operate in its littoral waters in the Bay of Bengal. Such escalating scenarios have grave implications for Northeast India from clandestine arms shipments that pass through these waters for the insurgent groups in the region. Contraband arms shipments seized in the past from Chittagong port and Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh originated through arms traffickers in Cambodia and Thailand ports. The coastal border points between Bangladesh and Myanmar have become a haven for contraband arms transit due to inadequate patrolling of their huge coastline in the past by these two countries. These shipments can land on the coasts of South Bangladesh and Northwest Myanmar and then smuggled inland in smaller consignments into Northeast India. The neighboring transit state in Myanmar namely Rakhine has rampant ethnic strife and Chin state has ethnic insurgencies and is not fully controlled by the Myanmar government.

Contiguous to India and Myanmar in Southern Bangladesh several inactive Rohingya militant groups such as the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO) are located out of the Cox’s Bazaar District of Bangladesh. The RSO has the support of terrorist groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan including the Hizb-ul Mujahideen of Jammu and Kashmir. The larger Arakan Rohingya National Organization (ARNO) organized all the different Rohingya insurgents into one group with alleged links to Al Qaeda.5 Taliban instructed military training camps have been spotted across the coastal border in Northern Rakhine state, Myanmar. These organizations have the support of the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami and its allies, whose members have been convicted for crimes of arms trafficking for the ULFA and the NSCN (IM).6 Pakistan’s ISI has also been reportedly implicated in facilitating the shipment of contraband arms through the Bay of Bengal meant for northeast insurgent groups.

Figure 3 – The Northeast India Connections

Source: Namrata Goswami

There have been reports circulating in the local press of Myanmar of China pressing its proxy militia aka United Wa State Army (UWSA) soldiers from North Myanmar to be deployed in strength along the new Kyaukpyu-Kunming pipeline for security. If such a scenario proves true on the ground, that would make any Indian security analyst sit up and take notice because of the UWSA’s infamous record of drug trafficking and contraband arms supplied to Northeast insurgents. Ironically, if China backed elements in Myanmar do get access to the Northeast’s borders, insurgent groups may have no further worries of elaborate transportation for purchased Chinese ordnance from Norinco and its illicit franchises in Wa state.

India needs to put in place a well-coordinated approach to secure the maritime and land neighborhood of the Bay of Bengal and Northeast India. This would include strengthening naval and coastal patrol assets in the littoral waters off the Andaman and Nicobar islands as well as enhanced strategic assets at the Northeastern borders opposite the ‘second coast’.

India has to work with Bangladesh, which faces a huge national security threat as the landing zone of trafficked arms through the Bay of Bengal by conspiring foreign terrorist organizations operating from its soil with support of local elements. The Myanmar government is challenged by insurgent militias still running loose, who are aided and abetted externally for short sighted strategic gains inside the country. India needs to support Myanmar in establishing the firm rule of the laws of its government throughout its length and breadth. India would need earnest diplomatic efforts to push relations with both Bangladesh and Myanmar in a mutually supportive security partnership against common foes of all the legitimate stakeholders in this strategic theatre.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. Lindsay Hughes, “Examining the Sino-Indian Maritime Competition: Part 3-China Goes to Sea”, January 22, 2014 at http://www.futuredirections.org.au/publications/indian-ocean/1507-examin… (Accessed on May 05, 2014)

- 2. Ibid

- 3. Aung Zaw, “Full Steam Ahead”, The Irrawaddy, 17/5, August, 2009 at http://www2.irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=16448 (Accessed on May 16, 2014).

- 4. Aung Zaw, “Is Burma China’s Satellite State? The Answer is Yes”, BurmaNet News, May 27, 2011 at http://www.burmanet.org/news/2011/05/27/irrawaddy-is-burma-chinas-satell… (Accessed on May 12, 2014).

- 5. See WikiLeaks cable on ARNO at http://www.wikileaks.ch/cable/2002/10/02RANGOON1310.html (Accessed on May 19, 2014).

- 6. Hiranmay Karlekar, “ The Great Chittagong Arms Haul and India”, The Pioneer.