A no-deal Brexit and its implications

- February 22, 2019 |

- Issue Brief

With the Brexit deadline getting closer, Britain is on the verge of a no-deal exit from the European Union (EU). The British Parliament’s rejection of Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit deal and the EU’s subsequent ruling out of renegotiation of the agreement leave the UK on a path toward a no-deal divorce. If the ongoing negotiations fail to agree on terms of withdrawal before March 29, 2019, or the UK decides to revoke the Brexit proposal, Britain may well break away from the EU without any negotiated agreement on future relationship. A no-deal would have enormous impacts not only on the economic prospects of the UK and Europe but in the realms of security and rights of the citizens as well.

With the Brexit deadline getting closer, Britain is on the verge of a no-deal exit from the European Union (EU). The British Parliament’s rejection of Prime Minister Theresa May’s Brexit deal and the EU’s subsequent ruling out of renegotiation of the agreement leave the UK on a path toward a no-deal divorce. If the ongoing negotiations fail to agree on terms of withdrawal before March 29, 2019, or the UK decides to revoke the Brexit proposal, Britain may well break away from the EU without any negotiated agreement on future relationship. A no-deal would have enormous impacts not only on the economic prospects of the UK and Europe but in the realms of security and rights of the citizens as well.

Why Britain voted to leave the EU?

Though Britain’s relationship with its European partners was historically complicated, Brexit discourse became popular in the UK only after the Eurozone economic crisis. When the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was formed in 1951, and the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, as a hard Eurosceptic, Britain disassociated itself with both projects. Finally, when the UK applied for EEC membership in 1961, the membership became a reality only in 1973 due to French opposition. However, two years later in 1975, the UK held a referendum on its association with the EU, and 64 per cent voted in favour of remaining in the economic bloc.1 This scepticism and love-hate relationship continued thereafter and finally to the Brexit vote in 2016.

British resentment towards the EU was the result of the interplay of three main factors — economic insecurity, populist nationalism, and British exceptionalism.2 The financial crisis that began in 2008 led to economic stagnation in Europe as a whole and the EU’s inability to manage the crisis reinforced the argument that it is a dysfunctional economic entity. The crisis and its consequences, such as increasing unemployment, inequality, north-south economic divide and the flaws of the euro, damaged the case for the EU.3 During financial distress, the EU member states not only realized the fragile nature of European institutions but also worried about the fate of their economies under EU’s direction. This led countries like the UK to rethink their association with the EU.

Populist nationalism across Europe accompanied by public unrest against immigration was the second trigger. The general distrust against multilateral institutions and liberal values in the last few years encouraged the emergence of a new but strong Eurosceptical group in English society.4 In addition, Britain’s post-imperial identity crisis and the discourse of British exceptionalism also led to the Brexit vote. Firstly, the exceptionalist discourse dichotomised the ‘British’ and ‘European’ identities. Then, it “generated a range of Eurosceptical political discourses that attempted to rede?ne the meaning of ‘Britain’, ‘Britishness’ and essentially fuelled ambivalent and negative public attitudes towards EU.”5

All these developments together resulted in the British government’s decision to hold a referendum and on June 23, 2016, the British voted to leave the EU by 52 to 48 per cent. The poll sent shockwaves across Europe, and beyond. The EU initially hoped that the UK would stay in a united Europe. But, pursuing the popular decision to leave, in March 2017, the British government invoked Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union and officially began the Brexit process.

In continuation of the exit process, after months of negotiations and consultations, in November 2018, the UK and EU reached an agreement on Brexit. The agreement sets the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, ensures an orderly departure and offers legal certainty once the Treaties and EU law will cease to apply to the UK. The draft withdrawal agreement mainly focused on five areas — citizens’ rights, separation issues, financial settlement, the border between the Republic of Ireland and the British territory of Northern Ireland, and the transition period.6 The agreement protects the rights of over 3 million EU nationals in the UK and 1 million UK citizens in EU countries to live, work and get social security benefits. The provisions on separation issues ensure a smooth winding-down of current arrangements on goods placed on the market, customs, intellectual property rights, police and judicial cooperation, and Euratom etc. The financial agreement assures that the UK and the EU will honour all financial commitments initiated while Britain was a member of the EU. The Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland sets out an operational ‘backstop’ solution for avoiding a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.7 The deal also agreed upon a transition period, until the end of 2020, during which the EU will treat the UK as a Member State, except participation in the EU institutions and governance structures. Later, the agreement was endorsed by the UK government and 27 EU member states and approved by the European Parliament. All that was required was the final seal of approval of the agreement from the British parliament.

Possible Brexit Scenarios

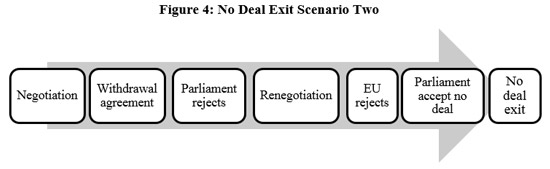

There were four possible exit scenarios for the UK at the beginning of the negotiations — exit based on a withdrawal agreement, exit without any agreement, and request for an extension of the time period for consultations or choosing to remain in the EU.8 However, as the negotiations are entering the end game, the UK appears headed towards a no deal exit, by default or design.

Exit with a deal had two possibilities. First, the UK concludes a withdrawal agreement with the EU and the British Parliament accepts it. Second, the British Parliament rejects the deal and asks the government to renegotiate it, and the EU agrees to renegotiation.9 But three recent developments, the British Parliament’s rejection of the deal and its demand that the deal be renegotiated and the EU’s dismissal of renegotiation, have virtually ended both possibilities.

The British Parliament’s rejection of the withdrawal agreement has already ruled out the possibility of an orderly exit (Figure 1). Even the plausibility in Scenario Two (Figure 2) has been ruled out by the EU’s rejection of the idea of renegotiating the withdrawal agreement. Responding to the British Parliament’s vote to renegotiate, Jean-Claude Juncker, European Commission President, said that the vote has increased the risk of a no-deal exit. He further clarified that the “EU will stick to the pledges made to Ireland on the border. It goes to the heart of what being a member of the EU means. Ireland’s border is Europe’s border, and it’s our union’s priority.”10 Moreover, since the British Parliament objected to one of the central terms of the agreement, the ‘Northern Irish backstop’11 the room for manoeuvre for the British government is limited.12

The two options left before the UK other than a no deal exit are revocation or extension of Article 50. Considering the political climate both in the UK and the EU, securing either is more difficult than a no deal exit. The revocation of Article 50 means withdrawal of the notice to the EU that the UK is leaving the Union. What makes this an attractive option is that the UK can do this unilaterally but after gaining the support of Parliament. However, “this is hard to sell to the electorate, especially to potential Conservative voters, who see their party as the one that has to deliver Brexit and would punish what they consider as backsliding.”13 On the other hand, the extension of negotiation requires the unanimous consent of all 27 EU member states. The likelihood of such a development is also limited since there is strong opposition in the EU about giving more time to Britain to sort out its domestic politics.

Moreover, since extending the deadline would likely clash with European parliamentary elections scheduled in May 2019, one can only anticipate a short term extension to avoid the costs of a chaotic British exit. Guy Verhofstadt, a European Parliament member and one of the Brexit negotiators, affirmed that “what we will not let happen, deal or no deal, is that the mess in British politics is again imported into European politics. While we understand the UK could need more time, for us it is unthinkable that article 50 is prolonged beyond the European elections.”14 An extension beyond the European Parliamentary elections technically means the UK’s participation in voting and further complications in the Brexit process.

Implications of a No Deal Brexit

The British exit from the EU, either with or without a deal, will have an enormous impact on the economic prospects of the UK and Europe. In the short-run, the key areas that will be affected by a disorderly exit include EU-UK trade relations, the EU budget, the Irish border, and the rights of citizens.15 The long term consequences of a no deal exit are graver and may prove irreparable.

According to various estimates, the UK will be economically worse-off outside of the EU. The government’s own assessment says that for the next 15 years, economic growth will be 9.3 per cent lower without a deal.16 In a no deal scenario, the UK and the EU are assumed to apply the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff plan, which means that tariffs will potentially rise by three per cent and 20 per cent of the value of the trade for manufactured goods and agri-food, respectively.17 Moreover, non-tariff barriers are expected to rise to between six and 15 per cent of the value of trade for goods and four to 18 per cent for services (See Table 1).

|

Channels |

No deal scenario |

FTA scenario |

EEA-type scenario |

|

Tariffs |

20 (Agri-food) 3 (Manufactured goods) |

Zero tariffs |

Zero tariffs |

|

Non-Tariff Barriers |

Customs administration costs and delays |

Customs administration and rules of origin costs, and delays |

Customs administration and rules of origin costs, and delays |

|

Significant additional barriers in goods and services. Goods: 6 to 15 Services: 4 to 18 |

Additional barriers to goods and services trade. Goods: 5 to 11 Services: 3 to 14 |

No additional barriers to goods and services trade. Goods: 3 to 7 Services: 1 to 3 |

Source: Government of UK18

The UK’s imports and exports will also be affected by increases in trade costs and a fall in domestic incomes and demand. As per the government estimates, in a no deal scenario, UK exports to the EU would decline by 35 per cent and imports from the EU by about 39 per cent (See Table 2). Lawless and Morgenroth estimate a fall of the EU27’s exports to the UK by 30 per cent and of the UK’s exports to the EU27 by 22 per cent in the post-Brexit scenario.19 International trade figures compiled by the United Nations and the World Bank show that British exports to the EU would be hit by an annual $7.6 billion in new tariffs under current WTO rules.20 Higher import rates would also lead to inflation and lower the standard of living for UK citizens. Many foresee a sudden fall of the sterling by 10 per cent if there is no deal. Since the EU27’s exports to the UK constitute only 2.6 per cent of EU GDP, the long-term impact of a no deal Brexit on the EU27 would be lesser compared to the UK.

|

|

No deal (% in average) |

FTA |

EEA |

|

UK total trade |

-37 |

-25 |

-6 |

|

UK exports to EU |

-35 |

-24 |

-6 |

|

UK imports to EU |

-39 |

-26 |

-8 |

|

Impact on economic output (measured by GDP) |

-7.6 |

-4.9 |

-1.4 |

Source: Government of UK

How the no deal exit affects the 1.3 million UK citizens living in EU 27 and 3.5 million EU nationals living in the UK is another significant concern. In the event of a chaotic Brexit, the future of UK nationals will depend on individual member states’ rulings and regulations. Though the European Commission asked member states to take a generous approach to UK nationals who are already resident in their territory, the decisions and regulations will pan out depending on the relationship between the UK and these countries. The legal situation of EU citizens residing in the UK is also not clear. The UK government has declared its intention of allowing visa-free travel for the EU27 citizens for short stays for purposes of tourism and business. However, given the fact that there is little progress in this area, the issue will be an immediate headache for both the UK and the EU.

A no deal exit would bring multiple challenges on the security front as well. Security agencies in UK warn of a higher risk and impact of terrorism and cross-border crime in case of a no deal. The negotiated exit deal includes agreement on using criminal records data, alerts on wanted suspects, DNA, fingerprints, airline passenger information, etc.21 A disorderly exit would harm all these arrangements. On the other side, the UK is a leader and net contributor on intelligence and security matters within Europe and a no deal Brexit would affect not only European security but EU’s role in global affairs. The UK is EU’s top spender on defence and has specialist capacities to contribute towards EU military assets. For instance, the UK accounts for “around 50 per cent of heavy transport aircraft as well as more than 25 per cent of all heavy transport helicopters among the EU member states.”22 Moreover, a no deal Brexit will decrease EU global humanitarian aid by up to three per cent, and the EU could lose between 10 and 13 per cent of its world aid share.23

Another significant challenge that the UK would face in a no-deal scenario is renegotiating the international agreements. According to the Financial Times, after exit, the UK will need to renegotiate about 759 treaties, covering trade in nuclear goods, customs, fisheries, trade, and transport.24 It requires the approval of almost 132 parties. Given the current political context and world leaders’ rapidly changing approach to liberalization, it will prove to be a laborious process for the UK to get these accords renegotiated smoothly. To give just one instance, in case of a no deal, the UK must renegotiate its 44 agreements with the United States, including treaties such as the EU-Euratom nuclear accord that require Congressional approval.

What Britain’s No Deal Exit Means for India

India sees the British exit as an opportunity to expand its trade and economic relations with the UK. British and Indian officials have been signalling that Brexit will make the conclusion of a bilateral free trade pact much easier.25 A report by the Commonwealth noted that “given the slow pace of negotiations over a trade deal with the EU, Brexit provides a fresh opportunity to India to strengthen its economic relationship with the UK through an India–UK trade and investment agreement.”26 According to the PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Brexit would bring about a situation where in the UK and EU compete for trading with India and enter into long term relationships with increased growth of trade.27

Though Brexit would change the approach of both the UK and EU towards India, it does not mean that Brexit would inevitably lead to the UK and the EU signing free trade agreements with India. Brexit with or without a deal would not affect contentious issues like the delays in the UK-India and the EU-India free trade agreements. For instance, one of the most significant issues in the UK-India FTA negotiations is labour mobility. India has been asking for an ease in visa rules but the UK has been hardening its stance on the issue. The recent exclusion of India by the UK Home Office from a new list of low-risk countries with relaxed student visa rules is a case in point.

Similarly, Brexit would not have any significant impact on the stalled EU-India FTA negotiations. For instance, considering the immigration crisis in EU and resentment towards migrants, India’s demand for liberalisation of services in cross border trade and people’s mobility will continue to be contentious issues. The EU’s request for a provision to challenge India in front of an international tribunal in case of conflict is another reason for the impasse. In this case, also, Brexit could not have any significant role to play.

On the other side, a no deal Brexit and the uncertainty it produces would have many adverse impacts on the Indian economy in general and Indian businesses in the UK in particular. For instance, at present, roughly 800 Indian companies operate in the UK. The UK serves as an entry point for many Indian companies to the European market. A disorderly British exit would shut the direct access of these companies to the EU market. That may force some of the companies to relocate or shut down their businesses.

Finally, the uncertainty of a no deal scenario and risk aversion tendencies across markets can further depreciate the already fragile rupee. Economists note that the US Dollar would be the only currency that benefits from a hard Brexit and the subsequent uncertainty in global markets. Such an outcome will not only affect the pound sterling but the currencies of emerging markets, including the Indian rupee, as well. A no deal scenario will therefore have an adverse impact in the short term, even if, in the longer term, Brexit would be an opportunity for India to reset its trade and economic relations with the UK and the EU.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. UK Parliament, ‘Referendums held in the UK,’ https://www.parliament.uk/get-involved/elections/referendums-held-in-the…

- 2. Graham Taylor (2017), Understanding Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union, Warrington: Emerald Publishing Limited (2017), p. 4.

- 3. George Friedman, ‘3 Reasons Brits Voted For Brexit’, https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnmauldin/2016/07/05/3-reasons-brits-voted-for-brexit/#3e8f23a01f9d; Also see Rajeesh Kumar (2014), et al. Eurozone Crisis and the Future of Europe: The Political Economy of Further Integration and Governance, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- 4. Note 2, p.4.

- 5. Ibid.p.4.

- 6. European Commission (2018), ‘Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union,’ https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/draft_withdra…

- 7. European Commission (2018), ‘Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland,’ http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-6423_en.htm

- 8. Guntram B Wolff, ‘What does a possible no-deal Brexit mean?’http://bruegel.org/2019/01/what-does-a-possible-no-deal-brexit-mean/

- 9. Jill Rutter and Joe Owen, ‘Autum Surprises: Possible Scenarios for the next phase of Brexit,’ IFG insight, August 2018, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/…/brexit-scena…

- 10. ‘Juncker Says Chance of No-Deal Has Increased: Brexit Update,’ Bloomberg, January 30, 2019, https://www.bloombergquint.com/politics/eu-not-prepared-to-renegotiate-d…

- 11. British withdrawal agreement from EU includes a protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland, which contains the provisions on so-called “backstop”, solution for avoiding a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. For more details, see Article 166, Protocols and Annexes ‘Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, ‘ https://www.europa-nu.nl/9353000/d/OntwerpVerdragBrexit.pdf

- 12. Ibid.p.4.

- 13. Fabian Zuleeg, ‘One step forward, two steps back: Towards no deal by default or design,’ Discussion Paper, European Policy Centre, 28 January 2019, p.2.

- 14. Guy Verhofstadt, https://twitter.com/guyverhofstadt/status/1085458645280788482?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7 Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cnbc.com%2F2019%2F01%2F18%2Fbrexit-extension-could-be-a-problem-for-…

- 15. These are the major issues discussed in the EU-UK agreement on withdrawal and therefore will be effected by the no deal exit significantly. A no deal exit simply means, no agreement on these issue areas.

- 16. Government of UK, ‘EU Exit: Long-term economic analysis,’ November 2018 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploa….

- 17. Ibid, p. 20.

- 18. Ibid, p. 25.

- 19. Martina Lawless and Edgar Morgenroth (2016), ‘The Product and Sector-Level impact of a hard Brexit across the EU,’ ESRI, Working Paper No 550, p.4.

- 20. The Guardian, ”No deal’ Brexit would mean £6bn in extra costs for UK exporters,’ https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/feb/20/no-deal-brexit-would-mea…

- 21. Joanna Dawson, ‘Brexit: implications for national security,’ Briefing Paper Number CBP7798, 31 March 2017, https://www.parliament.uk/commons-library

- 22. Lee D. Turpin, The Military Dimension of Brexit: A No-Deal on Defence?http://dcubrexitinstitute.eu/2018/08/the-military-dimension-of-brexit-a-…

- 23. European Parliament, ‘Possible impacts of Brexit on EU development and humanitarian policies,’ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/578042/EXPO_STU%2…

- 24. Financial Times, MAY 30, 2017 ‘After Brexit: the UK will need to renegotiate at least 759 treaties,’ https://www.ft.com/content/f1435a8e-372b-11e7-bce4-9023f8c0fd2e.

- 25. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/india-uk…

- 26. Rashmi Banga (2016), Brexit: Opportunities for India, The Commonwealth Secretariat Emerging Issues Briefing Paper, http://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/brexit-opportuniti…

- 27. PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry (2016), ‘Brexit Impact on Indian Economy,’ Working Paper No. 43, http://phdcci.in/live_backup/image/data/Research%20Bureau-2014/Economic%…