Defence Budget 2020-21

- February 12, 2020 |

- IDSA Comments

The biggest reform in higher defence organisation since independence has been the appointment of a Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), who heads the newly-created Department of Military Affairs (DMA) within the Ministry of Defence (MoD). The DMA, once fully operational, will deal with all three wings of the armed forces and focus on promoting jointness in procurement, logistics, transport, training, support services, communications, repairs and maintenance; ensuring optimal utilisation and rationalisation of infrastructure; and promoting the use of indigenous equipment by the defence services.1 However, the slowdown in economic growth not only seems to have cast its shadow on the allocation of the defence budget for 2020-21 but has also compounded the challenges for the country’s first CDS.

Defence Budget 2020-21

Defence budget, as commonly understood, consists of defence revenue and defence capital demands, i.e., two of the four demand for grants of the MoD, the other two being MoD (Civil) and Defence Pensions. However, with the creation of DMA, effective January 1, 2020, the defence budget for all purposes must include all four demand numbers of the MoD.

Prior to the creation of DMA, Service Headquarters (HQs) were ‘Attached Offices’ of the MoD. Hence, only two budget demands, i.e., Defence Services (Revenue) and Defence Services (Capital) were included in Defence Services Estimates (DSE, Volume I), popularly known and classified as Defence Expenditure. With DMA now a part of the MoD, leaving out Defence Pensions, the second-largest head of expenditure of the four MoD budget demands, not only keeps it out of focus but is also not consistent with the definition of Defence Expenditure.

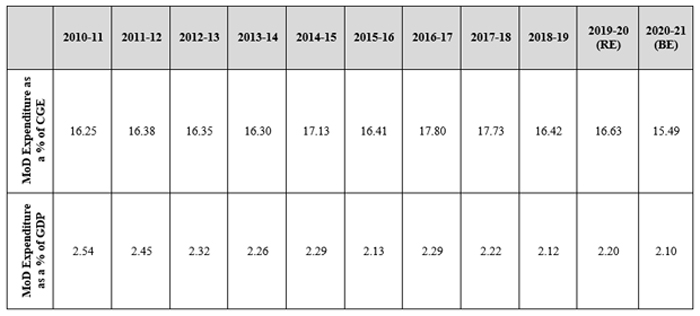

As stated earlier, the budget allocation this year reflects the economic stress that the country is passing through. The annual nominal GDP growth, which was in the range of 11 to 11.55 per cent (at current prices) since 2014-15, is down to 7.53 per cent in 2018-19 as per Revised Estimates (RE) of the budget. Despite government lowering the Central Government Expenditure (CGE) by nearly 90000 crore in 2019-20, the revised fiscal deficit at the RE stage has only gone up from the Budget Estimate (BE) target of 3.3 per cent to 3.8 per cent at the RE stage. What makes it worse is the declining trend in the share of defence expenditure as a percentage of both CGE and GDP, as seen in the table given below.

Source: All figures from the Union Budget documents.

The marginal increase in the percentage share of the MoD expenditure as a percentage of CGE (from 16.42 to 16.63 per cent) in 2019-20, despite decrease in the government expenditure by Rs. 87797 crore and GDP estimates for 2019-20 being revised downwards, is due to increased RE of all four demands of the MoD by Rs. 17809 crore, out of which defence revenue and defence capital amount to Rs. 11000 crore.

The above trend is further compounded by the following factors:

- As a major portion of the expenditure on capital acquisition is through imports, and platforms manufactured in the country have substantial import content, any adverse movement in the rupee-dollar exchange rate impacts the purchasing value of the available resources. It also impacts the maintenance expenditure as repair and overhaul of weapon platforms, and spares and fuel expenditure are also impacted by the adverse exchange rate (US$).

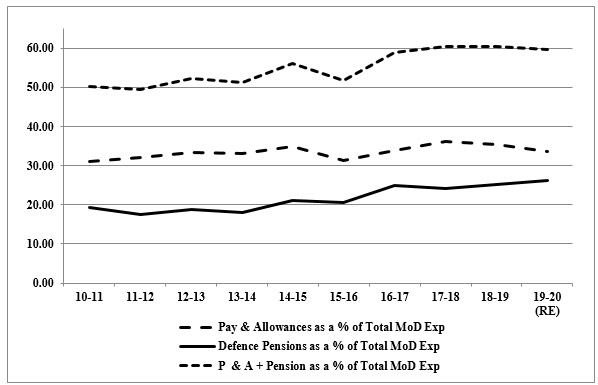

- The share of Pay and Allowances and Defence Pensions component has been increasing every successive year. About 60 per cent of the total MoD expenditure is on these two heads, both of which are first charges on the budget allocation.

Source: Union budget document Defence Services Estimates

That just leaves only 40 per cent of the budget to meet the modernisation, capital works (infrastructure), operational and maintenance (O&M) expenditure, training, revenue works (maintenance of infrastructure), transportation, research and development, and other miscellaneous expenditure. Their share has declined by 10 percentage points over the last decade. This adversely impacts both capability creation and maintenance of existing weapon platforms.

In the capital budget allocation (which caters for both modernisation and capital works i.e. infrastructure), the first charge is to meet the projected committed liabilities of contracts signed in the past years for the milestones likely to materialise during the year. In the year 2019-20, Rs. 1,13,667 crore was the amount projected for committed liabilities for modernisation and against this the allocation made at the BE stage was Rs. 80,959 crore.2 While slippages in the achievement of milestones in some contracts may provide some headroom, the remaining has to be managed by carrying forward the payments due to Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs). Reports indicate that MoD owed the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) alone about Rs. 14000 crore, as on March 31, 2019.3

The government has been aware of both budgetary allocations falling short of the needs and also its inability to meet the pressing needs for finding additional allocations for defence. The government in July 2019 had amended the terms of reference to enable the 15th Finance Commission to address serious concerns regarding the allocation of adequate, secure and non-lapsable funds for defence and internal security. Their term was further extended to submit the first report for the first fiscal year viz. 2020-21 and to extend the tenure for the presentation of the final report covering FYs 2021-22 to 2025-26 by October 30, 2020. Media reports indicate that the first report has been submitted to the government. MoD has suggested levying of a special cess and the Finance Commission is to set up an expert group, comprising representatives from the ministries of Defence, Home Affairs and Finance to consider the modalities for a non-lapsable fund.4 These issues are complex and despite best intentions, it may be challenging to find an optimal solution for them.

Way Forward

Given the situation, CDS does not seem to have the luxury of time on his side. It is, therefore, necessary for him to ‘make a virtue of necessity’. He has to immediately initiate some short-term measures while setting up expert groups to address and identify the long-term measures. There is no dearth of committee reports recommending optimisation of the defence expenditure.

The creation of DMA and the amended Allocation of Business Rules provide the CDS an opportunity to infuse greater ‘military efficiency’ by fulfilling one of his mandated duties, i.e., to “bring about reforms in the functioning of three Services aimed at augmenting combat capabilities of the Armed Forces by reducing wasteful expenditure.”5 Some measures are suggested in this regard:

- Rationalisation of Manpower: A large number of units/establishments/echelons have existed since before or were added after the Independence. Given increased automation and tremendous advancement in the field of information and communication technology (ICT), some of them may no more be of much relevance today. CDS’s mandate to promote and ensure jointness in the three services should bring about merger and consolidation of some of them into singular leaner entities. Existence of each organisation (unit establishments and echelons, whatever might be the nomenclature) must be reviewed periodically using ‘work study’ tools and any such entity which has outlived its necessity should be disbanded/merged/consolidated. The narrow ‘vacancies in the arm/branch/cadre/service’ approach has to give way to optimally or jointly managed assets, for example, aerial platforms like Dornier, Cheetah, Chetak and Advanced Light Helicopter (ALH), to name a few.

- Combatants-Civilian Manning-Outsourcing: The cost to the government taking into account the pay and allowances, accommodation, clothing, ration, leave entitlement, etc. and future pension liabilities in case of combatants are substantially higher than that of civilian employees in the same grade of pay. Hence, some of the services can be outsourced on a competitive basis at a much lower cost. Combatants need to man only positions that have an operational role, the other essential but not directly related to operations need to be manned by civilian defence employees.

- The Central Secretariat Service manpower in MoD at Group ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ levels neither bring any specialisation nor their tenure policy help in creating an institutional memory. The posts in all the departments of MoD, i.e., DMA, Department of Defence (DoD), Department of Defence Production (DDP) and Department of Ex-Servicemen Welfare (DESW) could be manned by the Armed Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) Cadre. The AFHQ cadre personnel manning civilian appointments in various directorates of Service HQ would over time acquire a better understanding of the subjects and work ethos and culture of the Defence Services. This will bring about optimal utilisation of the existing cadre, promote greater harmony and better understanding between the uniformed and the civilian bureaucracy, and bring to bear the institutional memory and infuse greater efficiency.

- Till such time the financial resources improve, new modernisation proposals for weapon systems/platforms that are under Buy (Indian-IDDM or Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured) and Buy (Indian) category should be given topmost priority and import of platform/systems should be a rare exception. Meanwhile, the modernisation process must continue. Private sector’s enthusiasm for the ‘Make in India’ initiative of the government serves as a wake-up call for the DPSUs. Lack of acquisition orders from MoD due to the paucity of budget will dampen their enthusiasm and may even permanently render some of them redundant. Hence, the limited resources available need to be used to sustain the efforts of the domestic industry (both public and private sector). This will also help the CDS in achieving one of the key mandates, which is, promoting the use of indigenous equipment by the defence services.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Cabinet approves creation of the post of Chief of Defence Staff in the rank of four star General”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, December 24, 2019.

- 2. “Capital Outlay on Defence Services, Procurement Policy, Defence Planning and Married Accommodation Project”, Para 1.8, Demand No. 20, Third Report, Standing Committee on Defence, Demand for Grants (2019-20), Seventeenth Lok Sabha, Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi, December 2019.

- 3. “HAL’s Cash in Hand Drops to 15-Year Low, Defence Ministry Owes it Rs 14,000 crore”, NewsCentral24X7, May 29, 2019.

- 4. Manu Pubby, “Levy special cess to meet capital expenditure, Defence Ministry recommends to Finance Commission”, The Economic Times, February 01, 2020.

- 5. Press Information Bureau, no. 1.