Defence Pension Reforms: Recommendations of the Past Committees and Commissions

The Union Budget 2020-21, presented to the Parliament on February 1, allocated a sum of Rs. 1,33,825 crore to the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to meet the pensionary liability of the retired defence pensioners. Representing 28 per cent of the MoD’s total 2020-21 budget, the pension allocation amounts to 4.4 per cent of the central government expenditure and 0.6 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP). In the last 10 years, the defence pension has witnessed the highest percentage increase among the MoD’s three major components, which include, apart from Defence Pension, MoD (Civil) and the Defence Services Estimates (DSE). Concerns have been expressed in some quarters that the pension budget is unsustainable for a balanced growth of India’s hard military capability.

The Union Budget 2020-21, presented to the Parliament on February 1, allocated a sum of Rs. 1,33,825 crore to the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to meet the pensionary liability of the retired defence pensioners. Representing 28 per cent of the MoD’s total 2020-21 budget, the pension allocation amounts to 4.4 per cent of the central government expenditure and 0.6 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP). In the last 10 years, the defence pension has witnessed the highest percentage increase among the MoD’s three major components, which include, apart from Defence Pension, MoD (Civil) and the Defence Services Estimates (DSE). Concerns have been expressed in some quarters that the pension budget is unsustainable for a balanced growth of India’s hard military capability.

This special feature identifies the key recommendations on defence pensions made in the past by various committees and commissions. The feature, however, begins with a brief statistical account of the defence pension, followed by a question as to why defence pension reform is the need of the hour. The special feature also touches upon the utilisation of job quotas available in various central government organisations by the ex-servicemen, in order to assess the scope for early retirement from the defence forces and their absorption in other sectors. However, the objective here is not to recommend any particular solution to mitigate the pension burden but to present a bouquet of solutions as suggested by various expert bodies in the past for a careful evaluation by the policymakers.

What We Know About Defence Pension

MoD’s pension budget caters to a number of retirement benefits, which include service pension, family pension, commutation, gratuity, leave encashment, monetary allowance for gallantry awards and arrears due to court judgements. Among these categories, pension (service pension and family pension) constitutes the bulk expenditure, accounting for 76 per cent of the total expenditure on defence pensions in 2018-19.1

As of April 2019, pension is provided to around 3.24 million pensioners (see Table 1), of which 2.59 million or 80 per cent are retired military personnel or their dependants and 0.60 million or 19 per cent are defence civilians and their dependants. About 46,869 or 1.4 per cent are not classified in the above two categories though efforts are on to find the right category for these group of pensioners. It is important to note that the total headcount of pensioners is based on actual counting since 2017-18, before which only assessed number was available.

|

Category |

Service Pensioners |

Family Pensioners |

Disability Pensioners |

Total |

|

Officers |

54,825 |

19,060 |

9,374 |

83,259 |

|

PBORs |

17,05,574 |

5,93,208 |

2,05,037 |

25,03,819 |

|

Defence Civilians |

3,47,779 |

2,54,004 |

— |

6,01,783 |

|

Unclassified |

46,869 |

|||

|

Total |

21,08,178 |

8,66,272 |

2,14,411 |

32,35,730 |

Source: IDSA Round Table on Defence Pension, February 14, 2020

Every year, a substantial number of defence personnel retire from the active service in the armed forces. Between 2011-12 and 2013-14, the number of retirees has increased from 49,827 to 57,507, an increase of 15 per cent (see Table 2). In 2013-14, among all the defence forces retirees, the Junior Commissioned Officers (JCOs) and Other Ranks (ORs) constituted nearly 97 per cent. On an average every year three categories of retirees – Sepoys, Naiks and Havildars and their equivalents – together constitute over 70 per cent of the total retirees from the armed forces.2

|

|

Officers |

JCOs/ORs |

Total |

|

2011-12 |

1,626 |

48,201 |

49,827 |

|

2012-13 |

1,643 |

53,446 |

55,089 |

|

2013-14 |

1,606 |

55,901 |

57,507 |

Source: “Report of the Seventh Central Pay Commission”, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, November 2015, p. 133.

Since the defence forces personnel begin their career early and also retire at a relatively young age than their civilian counterparts, a greater number of retirees are 60 years of age or less (see Annexure 1 for terms of engagement and retiring age of Personnel Below Officers Rank or PBOR). As of January 2014, of the total 1.86 million defence forces pensioners, 57 per cent were below 60 years, 35 per cent between 60 and 80 years, and eight per cent between 80 and 100 years (see Figure 1).

(Figure in Million)

Source: “Report of the Seventh Central Pay Commission”, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, November 2015, p. 400.

Why Reform Defence Pension

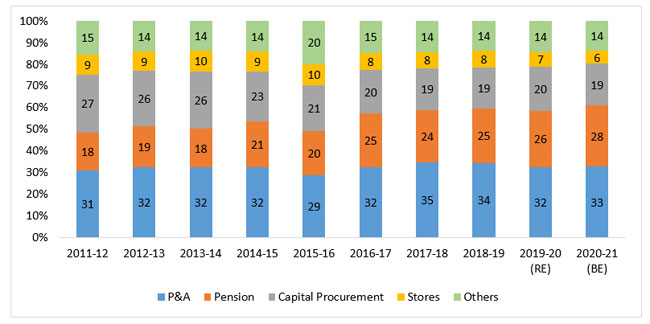

Figure 2 summarises the changing pattern among the key components of MoD’s expenditure: Pay and Allowances (P&A), Pension, Stores, Capital Procurement and other heads of expenditure. As can be seen, the share of the defence pension has increased the most, and together with P&A accounts for 61 per cent of the MoD’s total budget in 2020-21, up from 49 per cent in 2011-12. More significantly, nearly the entire increase in the pension’s share has come at the cost of the capital procurement, which together with Stores has dwindled by 11 percentage points from 36 per cent in 2011-12 to 25 per cent in 2020-21. In other words, the fast rise in the pension expenditure has a significant crowding out effect on the stores and modernisation, two major components that determine nation’s war-fighting ability. Needless to say, this does not augur well for India’s defence preparedness.

Sources: Figures compiled from Union Budgets and Defence Services Estimates (relevant years)

There are a number of reasons for the exponential growth in defence pension, which includes the implementation of the recommendations of the successive Central Pay Commissions (CPCs) and the One Rank One Pension (OROP) scheme, which has been implemented with effect from July 2014. The main contributing factor behind fast growth in the pension budget has, however, been the change in colour service which was effected twice in the 1960s and the 1970s. In 1965, the colour service for the vast majority of PBORs was increased from seven to 10 years, mainly to support rapid expansion of the army in the aftermath of the 1962 war with China.3 Again, in 1976, it was increased from 10 to 17 years. This change led to almost every retiree becoming eligible for a pension, in comparison to nearly 35 per cent who were eligible for a pension before 1965. This has also caused a quantum jump in the number of military pensioners with due effect on the pensionary expenses. In comparative term, the pension, which was part of the DSE till the mid-1980s, has increased significantly to account for over 40 per cent of the expenditure meant for the defence services (see Figure 3).

Source: Figures compiled from Union Budgets and Defence Services Estimates (relevant years).

If the fast rise in the pension budget has not already constrained India’s hard military capability development, the situation is unlikely to improve if no reform is carried out. It is a misnomer to assume that the pension budget’s share is likely to be drastically reduced and stabilise in the next 10-15 years when most of the current lot of the defence civilian pensioners (totalling 6,01,783 or 19 per cent of all the defence pensioners in 2019) would fade away. It is true that the number of civilian defence pensioners, presently covered under the Defined Pension Scheme (DPS), will gradually reduce to a negligible number over the next two decades. Their reduction would, however, have a little or no effect on the pension budget which is poised to surpass the P&A to become MoD’s single largest item of expenditure. Following are the four main reasons why the pension budget will continue to grow in the coming years:

First, the fading away of the current defence civilian pensioners will be partly offset by the new addition from the current serving lot of defence civilian employees, whose held strength is 3,98,422 as against a sanctioned strength of 5,85,476 as on March 1, 2018. Even if one assumes that the current held strength of the civilian employees does not grow further, and 40-50 per cent of the serving lot are still covered under the DPS, nearly 1,60,000 to 2,00,000 will gradually but eventually join the pensioner pool till around 2035 and will continue to draw pension/family pension for the next 15-20 years (i.e., till 2050-55), and possibly more, if the current life expectancy continues to improve further. Suffice it to say that India’s average life expectancy at birth, which is on a continuous rise since the early 1950s (see Table 3), is yet to reach a level seen in the developed countries.

|

Period |

Male |

Female |

Rural |

Urban |

Total |

|

1951-61 |

41.9 |

40.6 |

— |

— |

— |

|

1961-71 |

46.4 |

44.7 |

— |

— |

— |

|

1971-81 |

50.9 |

50 |

— |

— |

— |

|

1976-80 |

52.5 |

52.1 |

50.6 |

60.1 |

52.3 |

|

1981-85 |

55.4 |

55.7 |

53.7 |

62.8 |

55.4 |

|

1986-90 |

57.7 |

58.1 |

56.1 |

63.4 |

57.7 |

|

1991-95 |

59.7 |

60.9 |

58.9 |

65.9 |

60.3 |

|

2001-05 |

63.1 |

65.6 |

63.0 |

68.6 |

64.3 |

|

2006-10 |

64.6 |

67.70 |

64.9 |

69.6 |

66.1 |

|

2009-13 |

67.5 |

69.3 |

66.3 |

71.2 |

67.5 |

|

2011-15 |

66.9 |

70 |

67.1 |

71.9 |

68.3 |

|

2013-17 |

— |

— |

67.7 |

72.4 |

69.0 |

Note: —: Not Available

Sources: Central Pay Commission Report, National Health Profile 2019, Economic Survey 2019-20.

Second, all the present defence civilian employees, who are covered under the DPS, will eventually be replaced by new recruits under the National Pension Scheme (NPS), a Defined Contributory Scheme (DCS). The government’s contribution to the NPS for the civilian recruits, which may be less than what it would have otherwise spent on pension if the DPS were in place, will nonetheless add to the pension budget.

Third, the implementation of the OROP scheme and the CPC recommendations in future will provide a periodic spurt in the pension budget, especially that of the defence personnel. Suffice it to say that the implementation of 6th CPC more than doubled the pension budget in just two years while OROP and 7th CPC led to an increase of 46 per cent in pension expenditure in just one year.

Fourth, and the most important factor that would drive a high growth in the defence pension in the coming years is the ever-increasing pool of defence pensioners. This assessment is based on a higher life expectancy that the present and future pensioners are likely to enjoy and the absolute number of service pensioners to be added to the pensioner club. The increase in the life expectancy would result in fewer pensioners moving out of the government’s pension pool, while the annual addition of pensioners will keep the pool growing at a much faster pace.

As regards the number of pensioners, a simple calculation would show that the net increase in defence pensioners in the next 15 years would exceed today’s total number of civilian pensioners. It may be mentioned that at present nearly 60,000 add to the existing pool of defence pensioners which as of April 2009 totals 2.6 million. Assuming that 0.63 per cent4 of the existing defence pensioners are moved out of government’s pension liability every year, the net addition of defence pensioner is approximately 43,400 (60,000 minus 0.63 per cent of 2.6 million). Assuming everything else to remain constant, the net increase in the next 15 years would be around 6,51,000, which is little more than the total strength of the defence civilian pensioners in 2019. So, any possible ‘gain’ that would come due to fading away of the present defence civilian pensioners will be more than compensated by the increases in the number of defence pensioners.

Past Recommendations

Defence pension has been a subject of intense discussion for a long time, though not much has been done to reform it. In the past, several committees and government-appointed commissions have looked into the matter. Some of the salient reforms suggested by these committees/commissions are:

Kargil Review Committee

The Kargil Review Committee (KRC) set up in 1999 under the chairmanship of late K. Subrahmanyam was among the first few expert bodies that had emphasised the imperative of containing the defence pension, especially that of the Army. It had noted that “The Army pension bill has risen exponentially since the 1960s and is becoming an increasing burden on the national exchequer.”5 The main context of the committee’s discussion on pension was, however, the unfavourable age profile of the Indian Army. Emphasising that “The army must be young and fit at all times”, the committee had advised for a drastic reduction of the colour service to a period of seven to 10 years from 17 years, which had been the policy since 1976.6 The reduction in colour service, argued the committee, would not only improve the age profile of the army but also reduce the pension cost. While advising such a drastic step, the committee was also mindful of the consequences, especially those related to the career aspects of the personnel released after a few years of service in the armed forces.

To allay concerns and provide an assured career to the army personnel, the committee had made an equally drastic suggestion, as per which the manpower requirement of the army would be met through the para-military forces which would “undertake recruitment on the basis of certain common national military standards and then send those selected for training and absorption in the Army for a period of colour service before reverting to their parent para-military formations.”7 This indirect mode of recruitment for Army’s manpower needs was suggested to overcome the objection of the para-military forces which, as noted by the committee, have their own “ethos and traditions” and maybe chary of lateral induction of retired personnel who have been directly recruited and employed by the Army. More than 20 years after KRC made its recommendation, a view is yet to be taken by the government (see Annexure 2 for KRC’s observations on Colour Service and Recruitment).

Group of Ministers

The Group of Ministers (GoM), which was set up in 2000 to examine the KRC’s recommendations, had also made observations on two key manpower issues – age profile and lateral entry – that have an implication on the defence pension. Like the KRC, the GoM had also unambiguously voiced its concerns about the unfavourable age profile of the defence forces, noting that “there are problems relating to aspects of retirement age and command profiles in the armed forces.”8 The expert body had also reasoned that “[i]n order to ensure that the armed forces are at their fighting best at all times, there is a need to ensure a younger profile of the Services.”9 In other words, the GoM, like the KRC, had argued for a reduced number of colour service. Had this recommendation of the GoM been implemented in true letter and spirit, this would have had an impact on the pension as the reduction of the colour service below the pensionable service (of 15 years) would have led many to retire without a pension, like it was before 1976.

As regards the age profile, the government, in pursuance of the GoM report, had set up in 2001 a committee headed by A.V. Singh. The AV Singh Committee’s recommendations were, however, limited to the officer cadre of the armed forces. To improve the age and command profile of the officers, the committee had suggested time-scale promotion of officers of up to Lieutenant Colonel/equivalent rank and creation of nearly 2,650 senior-level posts at the level of Colonel and above ranks. It is important to note that the financial impact due to increase in the number of posts at the senior level and early promotion of officers was recommended to be neutralised by having 50 per cent of the officers cadre as Short Service Commission (SSC) officers.

However, the induction of SSC officers never reached the 50 per cent level as recommended by the AV Singh Committee. Moreover, in due course, nearly all male SSC officers were given permanent commission – a privilege which has now been extended to the female officers of all three services through successive interventions by the Supreme Court. So, the original intention of the AV Singh Committee in regard to reduction in age profile, and better promotion prospects and lower pension burden have not been realised.

Though the GoM in its report did not refer to the KRC’s indirect mode of recruitment, but it did refer to lateral entry as part of the solution for reduction of colour service, which in turn would have an impact on the pension burden. Considering the complexities involved in lateral entry from armed forces to other organisation, the GoM recommend the constitution of a high-powered committee to look into the “terms of engagement of soldiers, lateral entry into other organisations and resettlement policies.”10

Standing Committee on Defence

The Standing Committee on Defence of the 14th Lok Sabha took up the GoM recommendations including on the reduction of colour service and provisions for lateral entry into the para military force for detailed examination. Though the committee did not come out with anything new, it nevertheless brought to fore the “contentious and intractable” issues that have prevented any further progress. Some of the key issues highlighted by the committee relate to:

- Fixing the inter-se seniority of the transferees vis-à-vis original inductees of the Central Para Military Forces (CPMFs) without adversely affecting the latter’s promotion prospects.

- Disparities in the pay and allowances and perks of the CPMF, now known as Central Armed Police Force (CAPF), and Army transferees.

- Issue of reservation for backward classes, women and state-wise quota vis-à-vis no quota system in the armed forces.

- Adverse impact on the age profile of the CPMF due to lateral entry from the defence forces.

Central Pay Commission

The CPC, since its third report onwards, has been dealing with the pay, pension and other benefits of the armed forces. Of the five CPC reports that have examined the pay and perks of the armed forces, at least three commissions have made specific recommendations with a view to contain the burgeoning defence pension. Following are the 5th and 7th CPC recommendations that have a bearing upon defence pension.11

5th Central Pay Commission

The 5th CPC, which presented its report in 1997, is perhaps the first expert body to have openly talked about manpower issues of the armed forces in great detail. The commission’s manpower-related recommendations were based on a detailed study conducted by the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), now Manohar Parrikar IDSA, and interactions with three service chiefs, retired service chiefs and other experts. The highlight of the recommendation was restructuring of the armed forces with a 30 per cent reduction in manpower strength in a decade.12

It is worth noting that though pension was not the focus of the 5th CPC, it was nonetheless linked to the commission’s major recommendations as any downsizing of the armed forces will automatically bring down the future pension liability. The commission also made a number of other recommendations that have a relation with the pension. This include the reduction of colour service and lateral induction into both defence and non-defence sectors, withdrawal of the armed forces from the non-core functions and massive “civilianisation of posts in static, rear and administrate support organisations and workshops in the three services.”13 The latter recommendation assumes significance considering that the cost of a civilian employee (both while in service and also post-retirement) is less in comparison to a combatant.

7th Central Pay Commission

The 7th CPC presented its report to the government in November 2015. In a first, the commission made a direct reference to the NPS as a possible option to contain defence pension liability. Referring to the increase in pension liability, the commission had observed that “[i]n the context of Defence forces personnel, the annual addition of large number to the pool of retirees, the general increase in longevity, as also the proposed introduction of the One Rank One Pension scheme, will together lead to a huge increase in government’s liability towards defence pension.” It, therefore, suggested that the government may “explore the possibility of laying down a Defined Contribution Scheme for Defence forces personnel where the employee makes a contribution and a suitable amount is contributed by the government so that a sizeable corpus is built up.”14

On the issue of lateral entry into the CAPFs, the commission had examined it from the perspective of annual number of retirees in the defence forces, the ability to absorb them by the CAPFs and the hindrances in the implementation of the scheme which has been in discussion for a long time. In view of these, the commission recommended that:

- The primary focus on lateral entry into the CAPFs should be on personnel retiring from the ranks of Sepoys or their equivalents as opposed to personnel from others ranks;

- Sepoys after completion of seven years in the armed forces may be given an option to move to the CAPF with seniority and pay being protected;

- Those joining CAPF after seven years of service in armed forces may be given one-time lump sum amount amounting to 10.5 times the last pay drawn. After joining the CAPF they would continue till the retirement age and be covered under the NPS; and

- The vacancies of Constables in the CAPFs may be filled from Sepoys leaving after seven years.15

Utilisation of Reservation Quotas by Ex-Servicemen

To provide longer career prospects to the personnel retiring early from the armed forces, the government has mandated reservation of jobs that includes 10 to 24.5 per cent in various central government ministries/departments,16 public sector enterprises, nationalised banks and 100 per cent in the Defence Security Corps (DSC, see Annexure 3). It is worth noting that against a total 35,34,831 posts, excluding those in DSC17 , available in all the agencies as on June 2019, 4,27,830 posts (12 per cent) are available to be filled up by the ex-servicemen (ESM). However, the actual utilisation is a mere 68,502 or 1.94 per cent (See Annexure 4). Prima facie, it appears that lack of training is a major reason why ESMs are not able to qualify. The argument that the ESMs are age-barred by the time of their discharge from service is not tenable, as they enjoy age relaxation of three years plus the actual service years rendered in the military for reckoning of upper age limit.18

Conclusion

Reforming defence pension is no more an option but a compulsion considering its exponential growth in the past, which is likely to continue in the future if no reform is undertaken. It is, therefore, imperative for the government to recognise this reality and find a sustainable solution to it. Any reform initiative taken now will indeed start showing effect much later, possibly after a decade. However, the cost of doing nothing will have a far greater debilitating effect on India’s hard capability development than one could fathom.

Terms of Engagement and Retiring Age of PBORs19

| SL. No. | Rank | Army | Navy | Air Force | |||

| Terms of Engagement (In Years) | Retiring Age (In Years) | Terms of Engagement (In Years) | Retiring Age (In Years) | Terms of Engagement (In Years) | Retiring Age (In Years) | ||

| 1 | Sepoy/ Equivalent | 19-22 | 42 -48 | 15 | 52 | 17 -22 | 52 |

| 2 | Naik/ Equivalent | 24 | 49 | 19-22 | 52 | 19-24 | 49-52 |

| 3 | Havildar/ Equivalent | 26 | 49 | 25-28 | 52 | 25-28 | 49-52 |

| 4 | Naib Subedar / Equivalent | 28 | 52 | 30-32 | 52 | 28-33 | 52 |

| 5 | Subedar/ Equivalent | 30 | 52 | 34-35 | 57 | 30-35 | 52-57 |

| 6 | Subedar Major/ Equivalent | 34 | 54 | 37 | 57 | 33-37 | 54-57 |

Source: “Seventh Central Pay Commission Report”, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, November 2015, pp. 397-98.

Observations of the Kargil Review Committee on Colour Service and Indirect Mode of Army’s Recruitment

Para 14.14: The Army must be young and fit at all times. Therefore, instead of the present practice of having 17 years of colour service (as has been the policy since 1976), it would be advisable to reduce the colour service to a period of seven to ten years and, thereafter, release these officers and men for service in the country’s para-military formations. After an appropriate period of service here, older cadres might be further streamed into the regular police forces or absorbed in a National Service Corps (or a National Conservation Corps), as provided for under Article 51A(d) in the Constitution, to spearhead a range of land and water conservation and physical and social infrastructure development on the model of some eco-development battalions that have been raised with a fair measure of success. This would reduce the age profile of the Army and the para-military forces, and also reduce pension costs and other entitlements such as married quarters and educational facilities. The Army pension bill has risen exponentially since the 1960s and is becoming an increasing burden on the national exchequer. Army pensions rose from Rs. 1568 crores in 1990-91 to Rs. 6932 crores (budgeted) in 1999-2000, the equivalent of almost two-thirds of the current Army salary bill.

Para 14.15: The para-military and police forces have their own ethos and traditions and might well be chary of such lateral induction as has been proposed. The objection might be overcome were the para-military forces to undertake recruitment on the basis of certain common national military standards and then send those selected for training and absorption in the Army for a period of colour service before reverting to their parent para-military formations. The Committee is aware of the complexities and sensitivities involved in any such security manpower reorganisation. Nevertheless, national security dictates certain imperatives which the country may ignore only at its peril. The proposed reorganisation would make a career in the armed forces attractive on the basis of the lifetime employment offered by the two or three-tiered secondment formula.

- Reservation in Central Government Ministries/Department:

- 10 per cent direct recruitment posts up to the level of Assistant Commandant in Central Para Military Forces

- 10 per cent direct recruitment in post in Group ‘C’

- 20 per cent direct recruitment in Group ‘D’

- Reservation in Central Public Sector Enterprise

- 14.5 per cent in Group ‘C’ posts

- 24.5 per cent in Group ‘D’ post

- Reservation in Nationalised Banks

- 14.5 per cent in Group ‘C’ posts

- 24.5 per cent in Group ‘D’ post

- 100 per cent in Defence Security Corps

(Including 4.5 per cent for disable ESM/dependent of servicemen killed in action)

(Including 4.5 per cent for disabled ESM/dependents of servicemen killed in action)

Filled Rate against Reserved Quota for Ex-Servicemen (As on June 30, 2019)

|

Name of Organisation |

Classification of Posts |

Overall Strength (No.) |

Reserved Quota for ESM (%) |

Reserved Quota for ESM (No.) |

Posts Filled by ESM |

|

|

No. |

% |

|||||

|

Central Govt. Departments |

Group ‘C’ |

15,45,478 |

10 |

154548 |

6173 |

0.4 |

|

Group ‘D’ |

4,009 |

20 |

|

3 |

0.07 |

|

|

Central Public Sector Undertakings |

Group ‘C’ |

4,73,266 |

14.5 |

68624 |

4965 |

1.05 |

|

Group ‘D’ |

1,51,276 |

24.5 |

37063 |

695 |

0.46 |

|

|

Public Sector Banks |

Group ‘C’ |

2,89,505 |

14.5 |

70929 |

22935 |

7.92 |

|

Group ‘D’ |

1,21,973 |

24.5 |

17686 |

28150 |

23.08 |

|

|

Central Armed Police Forces |

Group ‘A’ |

8,634 |

10 |

863 |

64 |

0.74 |

|

Group ‘B’ |

56,830 |

10 |

5683 |

579 |

1.02 |

|

|

Group ‘C’ |

8,83,860 |

10 |

88386 |

4938 |

0.56 |

|

|

Group ‘D’ |

0 |

20 |

|

0 |

0 |

|

|

Total |

Group ‘A’ |

8,634 |

|

|

64 |

0.74 |

|

Group ‘B’ |

56,830 |

|

|

579 |

1.02 |

|

|

Group ‘C’ |

31,92,109 |

|

|

39011 |

1.22 |

|

|

Group ‘D’ |

2,77,258 |

|

|

28848 |

10.4 |

|

|

Grand Total |

|

35,34,831 |

|

4,27,830 |

68502 |

1.94 |

Source: “Re-Employment of Ex-Servicemen”, Unstarred Question No. 2735, Lok Sabha, Answered on December 04, 2019.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. IDSA Round Table Discussion on Defence Pension, February 14, 2020.

- 2. “Report of the Seventh Central Pay Commission”, Ministry of Finance, Government of India, November 2015.

- 3. See para 5.2 of the 34th Report of Standing Committee on Defence, 14th Lok Sabha, p. 57.

- 4. This is based on India’s average death rate. See “National Health Profile 2019”, Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India, p. 20.

- 5. See para 14.14 of the Kargil Review Committee Report, December 1999.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. GoM Report on Reforming the National Security System, February 2001, p. 112.

- 9. Ibid., p. 113.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. The 6th CPC has not been discussed here as its recommendations, especially those pertaining to colour service and lateral entry, were on similar lines and have been discussed elsewhere in the Special Feature.

- 12. “Report of the Fifth Central Pay Commission”, Vol. I, pp. 297-303.

- 13. Ibid, p. 302.

- 14. “Report of the Seventh Central Pay Commission”, no.2, p. 399.

- 15. Ibid.

- 16. See “Compendium on Reservation, Concessions and Relaxations for Ex-Servicemen in Central Government Services”, Department of Personnel and Training, Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India, February 2014.

- 17. Recruitment in the rank of Sepoys in the DSC, which has a personnel strength of over 30,000, is reserved for the PBORs. The armed forces personnel joining the DSC after retirement have two options in matters of pension. They can either add their former service to the service rendered in the DSC and take one pension for combined total length of service or can opt for their normal pension from their former service and start afresh in the DSC where they are entitled to a second pension after completing minimum 15 years of services in the organisation.

- 18. An ESM, who at the time of discharge from the military is 30 years old and has seven years of service, will be considered as 20 years old. See The Gazette of India, October 10, 2012.

- 19. The terms of engagement and retiring age prima facie look on a higher side. It needs to be examined.

- 20. “Re-Employment of Ex-Servicemen”, Unstarred Question No. 2735, Lok Sabha, Answered on December 04, 2019.