Is Northeast Poised for Lasting Peace?

- July 08, 2020 |

- Issue Brief

Summary: Almost all major insurgent groups in the Northeast have abjured violence and are engaged in peace talks with the Government of India. This has raised hopes that all contentious issues that plunged the region into decades of violence and poverty will finally be resolved, ushering in all-round peace and development. However, the indeterminate nature of the peace talks, active cadres of anti-talk factions, poor implementation of ceasefire rules and persistent anti-foreigner sentiments can potentially damage the fragile peace achieved in the region.

Summary: Almost all major insurgent groups in the Northeast have abjured violence and are engaged in peace talks with the Government of India. This has raised hopes that all contentious issues that plunged the region into decades of violence and poverty will finally be resolved, ushering in all-round peace and development. However, the indeterminate nature of the peace talks, active cadres of anti-talk factions, poor implementation of ceasefire rules and persistent anti-foreigner sentiments can potentially damage the fragile peace achieved in the region.

Since the beginning of the year, the Northeast has witnessed several positive developments which seem to harbinger peace in the region. To begin with, the decades-old Bodo insurgency came to an end with the signing of a Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) by the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) in January 2020 and complete disbandment of its armed cadres two months later in March.1 Further, on January 23, at least 644 cadres belonging to eight different militant outfits including the United Liberation Front of Assam-Independent (ULFA-I), the NDFB, the Kamtapur Liberation Organisation (KLO) and the Rabha National Liberation Front (RNLF) surrendered in Assam.2

This trend of insurgent groups abjuring violence and participating in peace parleys was witnessed last year as well when the National Socialist Council of Nagalim – Khango (NSCN-Khango) re-entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Union government and participated in the Naga peace talks.3 Similarly, the National Liberation Front of Twipra – Subir Debbarma (NLFT-SD) too agreed last year to renounce violence and enter the national mainstream.4

In fact, during the past few years, violence levels in the Northeast have reduced with many insurgent groups either entering into ceasefire agreements with the government or signing peace accords and subsequently disbanding themselves. Do these positive developments indicate that the Northeast region is finally poised for lasting peace, or are there issues that could create hurdles in the future?

Security Situation

Ethnic insurgency is one of the most significant challenges that India has faced in the Northeast. Starting with the Naga insurgency in 1956, various ethnic groups including the Meiteis, Mizos, Tripuris and Assamese have successively risen to assert their distinct identities and political aspirations. Past efforts by the government to negotiate peace with insurgent groups and accommodate their aspirations within the constitutional framework of the Indian Union failed to usher in lasting peace due to three main reasons.

First, except in the case of Mizoram, sections of insurgent groups opposed to the talks invariably continued with their armed struggle. Second, peace accords with dominant tribal groups often triggered insecurities among the minor tribes, which, in turn, took up arms to protect and promote their interests. And third, the intra-ethnic conflicts among various tribes and sub-tribes. At the root of all conflict in the region is the issue of identity. Insurgencies in the Northeast have been of three types:

- Separatist insurgencies demanding independence.

- Autonomist insurgencies asserting sub-regional aspirations.

- Intra-ethnic conflicts among dominant and smaller tribal groups.5

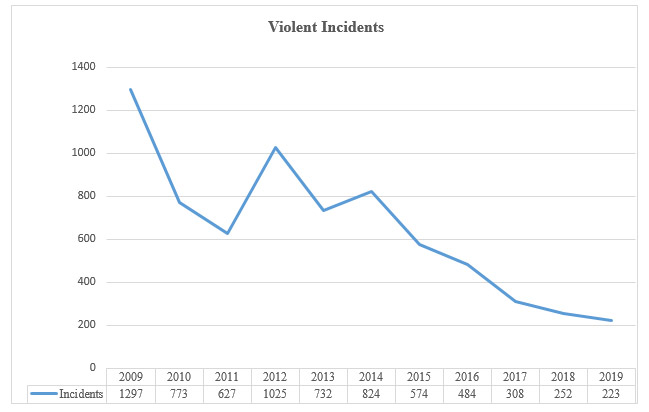

While these numerous insurgencies led to large-scale violence that peaked during the 1980s and the1990s, the situation began improving at the turn of the century. During the last 20 years, the level and intensity of violence have steadily declined. Whereas the number of violent incidents stood at 1297 in 2009, it declined by nearly six times to 223 in 2019 (see Graph.1).

Source: “Insurgency in Northeast”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2020.

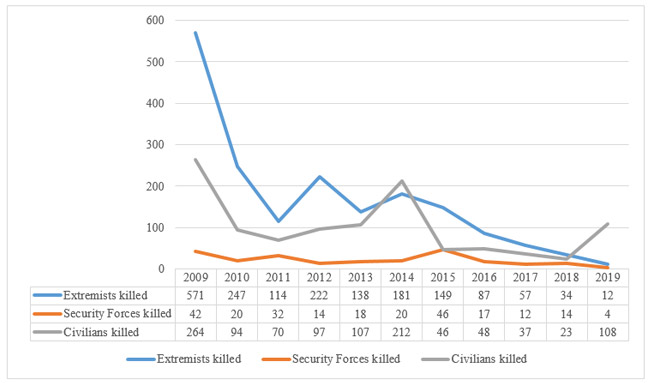

Similarly, the number of people killed – insurgents, security personnel and civilians, have also declined by nearly eight times, from 877 in 2009 to 71 in 2018. There was, however, an increase in the number of civilians killed in 2019 (see Graph 2).

Source: “Insurgency in Northeast”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2020.

States such as Sikkim, Mizoram and Tripura have become entirely free of insurgent violence. The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, or AFSPA, was removed from entire Tripura in 2015 and from Meghalaya in 2018, while in Arunachal Pradesh, areas under the Act have been reduced from 16 to four police stations along the Arunachal-Assam border. The Act, however, continues to be in force in Assam, Manipur (except the Imphal municipal area), Nagaland and three districts of Arunachal Pradesh (Tirap, Changlang and Longding).6 In Manipur and Assam, the Act is in force on the express recommendation of the respective state governments which have concurrent powers to declare the state or parts of it as a disturbed area under the AFSPA.

Status of Insurgent Groups

Today, almost all the major insurgent groups in the region, except the Meitei insurgents, have entered into a ceasefire or Suspension of Operation (SoO) agreements with the Union and/or state governments. They are engaged in peace talks with some even disbanding their armed cadres.

In Nagaland, all factions of the NSCN have signed ceasefire agreements with the Union government. The NSCN – Issak Swu-Muivah (NSCN-IM) signed the ceasefire agreement in August 1997, which was extended indefinitely in 2007. Since then, the other Naga factions have also signed the ceasefire agreements, the last being NSCN-Khango, which did so as recently as April 2019.7 The Union government has been conducting peace talks with all the Naga factions, albeit separately. Furthermore, in November 2017, six Naga insurgent groups belonging to various factions of the NSCN and the National Naga Council (NNC) came together under the Naga Nationalist Political Groups (NNPGs) and formed a Working Committee to negotiate as one block with the Centre.8 The NSCN-Khango joined the Working Committee in 2019 as the seventh member.

Likewise, in Assam, the ULFA – Pro-Talk (ULFA-PT) signed the SoO agreement in September 2011 with the state government and entered into peace negotiations with the Union government. As far as the Bodo militant outfits are concerned, all factions of the NDFB have signed ceasefire agreements with the Government of India – NDFB (Progressive) in 2005 and NDFB (Ranjan Daimary) in 2013.9 On January 16, 2020, the Saoraigwra faction of the NDFB too signed a tripartite SoO agreement with the Union as well as the state government.10 It was followed by the signing of the MoS on January 27, 2020 between four factions of the NDFB – Progressive, Ranjan Daimary, Dhiren Boro, and Saoraigwra – along with the All Bodo Students Union (ABSU), and the Union government and the Assam state government.11 Subsequently, 1615 cadres belonging to various factions of the NDFB laid down arms on January 30, 2020.12 Thereafter, the NDFB disbanded its armed cadres on March 11, 2020.13

Earlier, smaller militant groups such as the United People’s Democratic Solidarity (UPDS) representing the Karbi tribe and Dima Halam Daogah (DHD) representing the Dimasa tribe had disbanded themselves after signing the MoS with the Government in November 2011 and October 2012, respectively. The Karbi Longri NC Hills Liberation Front (KLNLF) had signed a MoS way back in 2010. In Meghalaya too, the Achik National Volunteer Council (ANVC) had signed a MoS with the Union government and disbanded itself in December 2014.14

In Manipur, while the major Meitei groups have not signed any ceasefire agreement, the breakaway factions of the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP), the Manipur Army and the Kanglei Yawel Kanna Lup (KYKL) came together to form the United Revolutionary Front (URF) and entered into a ceasefire agreement with the Union government in 2013. In August 2008, 23 insurgent outfits (which later increased to 25) belonging to Kuki, Zo, Paite and Mhar groups had organised themselves under two umbrella organisations – Kuki National Organisation (KNO) and United Progressive Front (UPF) and signed the SoO agreement with the Manipur state government. Political dialogue with these two groups was initiated in June 2016.15 Recently, the KNO and the NNPG signed an accord on January 10, 2020 to end the inter-tribal conflict by recognising each other’s history and identity.16

In Tripura, the security situation has improved tremendously. Peace talks are on with the NLFT Biswamohan (NLFT-BM) since 2015. The fighting strength of the All Twipra Tiger Force (ATTF) has also diminished substantially with the arrest of the outfit’s chief Ranjit Debbarma in 2017.17 Furthermore, the Sabir Kumar Debbarma faction of the NLFT signed a MoS with the Union and the state government on August 10, 2019, with 88 of its cadres surrendering along with their weapons three days later.18

Reduction in Violence

Four main factors have contributed to compelling the various insurgent groups to give up violence and engage in peace talks. These are loss of safe sanctuaries, sustained counter-insurgency operations, appeals by civil society groups to shun violence, and largescale out-migration of youth from the region.

The first and most important factor is the loss of safe sanctuaries in neighbouring countries. Safe havens in Bhutan, Bangladesh and Myanmar had long helped the insurgent groups to regroup, recuperate and train as well as forge fraternal links with each other. The establishment of the United National Liberation Front of Western South East Asian (UNLFWSEA) is a case in point.19 The tide turned against the insurgent groups as New Delhi constructively engaged the neighbours, sensitising them of India’s security concerns, and as they promised not to allow their territories to be used for anti-India activities.20 Bhutan was the first to act by launching Operation All Clear in December 2003. During this operation, the Royal Bhutan Army uprooted the camps of ULFA, NDFB and KLO, killed or arrested 650 of their cadres, and forced another 500 or more to surrender.21

A change in the political dispensation in Dhaka in 2009 also dealt a body blow to the insurgency in the Northeast. Bangladesh not only shut down the insurgent camps located on its territory but also arrested several top insurgent leaders and handed them over to India. Prominent among them were Arabinda Rajkhowa of ULFA, Rajkumar Meghen of the United National Liberation Front (UNLF), Ranjan Daimary of NDFB (RD), Biswamohan Deb Burman of NLFT and Ranjit Debbarma of ATTF. According to the Border Security Force (BSF), there are currently no permanent camps of Indian insurgent groups in Bangladesh.22

Myanmar too has been cooperating with India since January 2019 when its army occupied the NSCN-K headquarters in Taga in the Sagaing Division and launched three coordinated military operations along with the Indian Army, codenamed Operation Sunrise, in the months of February-March and May-June 2019 and March 2020.23 Military action by the Tatmadaw has since forced many of the Assamese and Manipuri insurgents to cross back into India and surrender. The surrender of 644 militants belonging to eight insurgent groups including ULFA-I, NDFB, KLO and some Adivasi groups in January 2020 is a case in point.24 On May 14, 2020, Myanmar also handed over 22 insurgents belonging to the NDFB (S), KLO, People’s Liberation Army (PLA), KYKL, People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak – Progressive (PREPAK–Pro) and the UNLF, all of whom were imprisoned during Operation Sunrise.25

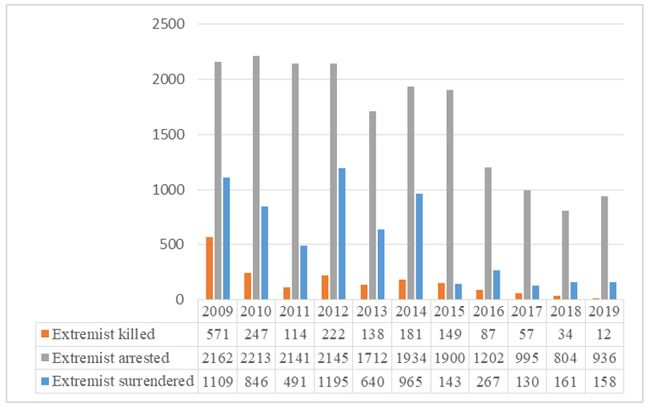

The second factor responsible for bringing down violence levels is the sustained nature of counter-insurgency operations carried out by the Indian security forces, which not only led to the killing of several insurgents including senior cadres but also the arrest and surrender of a substantial number of insurgents (see Graph 3).

Source: “Insurgency in Northeast”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2020.

These military operations also ensured that insurgent outfits could not carry out spectacular attacks to motivate their cadres or raise funds through donation or extortion. Sustained counter-insurgency operations have dealt a big blow particularly to the smaller insurgent groups, such as the Garo National Liberation Army (GNLA). An attractive surrender and rehabilitation scheme has also been instrumental in encouraging insurgents to surrender. First launched in January 1998, the scheme was revised in 2005 and again in April 2018 to make it more lucrative.26 Since 2018, a total of 2,578 rebels have reportedly surrendered, with the maximum number of 2,259 surrenders taking place in the first five months of 2020.27

Third, concerted appeals by the civic groups such as the Naga Hoho and Tatar Hoho in Nagaland, Meira Paibis, Keithals and Lup in Manipur28 as well as various church groups, mothers’ associations, literary societies, etc. to the insurgent groups to shun violence and embrace peace have also played a role in breaking the vicious cycle of violence in the region. For example, the Naga Mothers’ Association had reportedly played a role in the NSCN (I-M) signing the ceasefire agreement in 1997.29 Similarly, the Sanmilita Jatiya Abhibartan (SJA) had not only appealed to the Union government to begin peace parleys with the ULFA but also prepared the blueprint for talks on its behalf.30

Lastly, the large-scale migration of youth from the Northeast to the rest of India has also probably played a role in reducing the recruitment pool for the insurgent groups. During the last decade or so, youth from the region, in their bid to escape from poverty, unemployment and also insurgency, have been migrating in large numbers in search of job opportunities in major metropolitan cities and popular tourist destinations in the country.31 While there is no available official data on out-migration of youth from the region, a North East Support Centre and Helpline (NESCH) survey report released in early 2011 puts the number of migrants outside the Northeast at 414,850, a 12 fold increase between 2005 and 2011.32 In fact, the recent saga of migrant workers returning to their homes, witnessed during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, has revealed the large number of people that went out of the Northeast to work in different parts of the country.

A Lasting Peace?

Despite the improvement in security situation in the Northeast, there remain a number of issues that have the potential to increase the level of violence in the region. Some such key issues have been discussed below:

Indeterminate Peace Talks: The Union government has been engaged in peace negotiations with several insurgent groups in the region, but not much success has been achieved against some of them. For instance, the Naga peace talks have gone on for 18 years without any solution in sight. India cannot go beyond the framework of the Constitution even if it recognises the unique history of the Nagas. For its part, the NSCN (I-M) has had its own red lines. It could not altogether give up on its demand for sovereignty and a united Nagalim without anything concrete to show in return.

However, a “breakthrough” was reported in August 2015 only when the NSCN (I-M) dropped its earlier demand of sovereignty and integration of all Naga-inhabited areas. This led to the signing of the Framework Agreement which reportedly laid the principles for final settlement.33 However, further talks were stuck apparently on the group’s demand for a separate flag and a constitution.

Following an ultimatum from the Prime Minister that talks conclude by October 31, 2019, the last round of negotiations was carried out at the end of the same month. On the conclusion of the talks, while the NSCN (IM) representatives claimed that all outstanding issues have been resolved and only a few technicalities remain to be sorted out before the final agreement is signed, the Government of India did not concur with the statement and clarified that a settlement would be reached only after the consent of all stakeholders including the states of Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh is taken into consideration.34

The indeterminate nature of peace talks has given rise to rumours that the Nagas are frustrated and reverting to insurgent tactics. The absence of NSCN (IM) former Commander-in-Chief Phunting Shimrang in the last round of peace talks raised a buzz in the media that he was travelling to Yunnan. While a section of media speculated that he was trying to get China to put pressure on the Government of India to reach a final settlement, others believed that he was unhappy with peace talks and was trying to seek China’s support for the Naga cause.35

Similarly, peace talks with the Assam-based insurgent group such as the ULFA (PT) were supposed to have concluded by December 2019. It was reported that while talks between the Union government and the ULFA (PT) have more or less concluded, a deal could be signed only after legislation is passed to grant the scheduled tribe (ST) status to the six communities of Assam – Tai Ahom, Koch Rajbongshi, Chutiya, Moran, Muttock and the Adivasi tea garden workers, as demanded by the ULFA (PT). The Union Cabinet has approved the grant of ST status to the six communities, but there have been protests against the decision by both tribal and non-tribal groups. While the tribal groups feel that the inclusion of more communities in the ST category in Assam will reduce their share of benefits, the non-tribals believe that the decision will increase the percentage of tribals in the state, which in turn will lead to reservation of hitherto unreserved seats for tribals in the state assembly, to the detriment of their interests.36

Indulgence in Criminal Activities: Another fall out of the protracted peace talks is that the insurgents staying in designated camps feel increasingly demoralised and frustrated, as the absence of final settlement prevents a clear roadmap for their proper rehabilitation. Although the Government has revised its surrender and rehabilitation policy, but again in the absence of timely disbursement of funds many cadres leave the camps and go back to their villages. Unfortunately, it has been observed that many among them resort to criminal activities such as kidnapping for ransom and human trafficking to supplement their income.37 This is evidenced in the rise of crime graph in the affected states. In fact, the Governor of Nagaland R. N. Ravi had recently stated that the armed gangs run their “parallel government” thereby challenging the legitimacy of the state government. These gangs also resort to extortion, intimidation and commit violence with impunity.38

Poor Implementation of Ceasefire Agreements: Failure of the Union government to properly implement the ceasefire agreements has resulted in numerous turf wars and armed rivalries between the insurgent groups. Much of the violence reported in Manipur, Nagaland and Assam are because of fratricidal killings and attacks carried out by the insurgent groups. For example, over 1,800 Naga militants were killed in nearly 3,000 fratricidal clashes among various factions of the NSCN between 1997 and 2013.39 Further, the NSCN (IM) has been running a kidnapping and extortion racket despite being under a ceasefire agreement with the Government.40

Active Insurgent Groups in Myanmar: It is reported that currently around 2000-3000 insurgent cadres belonging to the ULFA-I and Meitei separatist outfits are still hiding at different locations in Myanmar.41 It is further reported that some like the UNLF and PREPAK are providing logistical support to the Arakan Army in Myanmar, which in turn allows them to build training camps in their strongholds in Rakhine and Chin states. Since these insurgent groups are involved in extortion and cross border smuggling, they are able to fund their stay in Myanmar. Furthermore, top insurgent leaders such as Paresh Baruah of ULFA-I, who has rejected several peace overtures, continue to evade the security forces and enjoy Chinese hospitality in Ruili.42 Till such time these anti-talk breakaway factions are brought to the negotiating table, insurgency in the region will continue and peace will remain a distant dream.

Anti-CAA Agitation: Last but not least, the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) in Assam’s non-scheduled areas has generated resentment against the Union government. It has provided an issue for insurgent groups such as the ULFA-I to mobilise and recruit youth. Another negative fall out of the agitation against CAA is the fear of the rise of Islamic radicalism in the state.

In Assam, there have been attacks against Muslims, who are perceived as illegal Bangladeshis. This, in turn, has radicalised some sections among the local Muslim community, who have formed armed groups such as the Muslim United Liberation Tigers of Assam (MULTA), Muslim Liberation Army (MLA)—formerly known as the Muslim United Liberation Front of Assam (MULFA), and Muslim Tiger Force of Assam (MTFA).43 If anti-migration sentiments persist in the state then apprehensions remain that local Muslim youth might get radicalised and join affiliates of international Islamist networks such as al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Conclusion

With reduced levels of violent incidents and overall death tolls, the security situation in the Northeast has indubitably improved. The ceasefire agreements and on-going peace talks with different insurgent groups have raised the hope that issues of identity assertion and overlapping territorial contestations, which had plunged the region into decades of violence and poverty, will finally be resolved, ushering in all-round peace and development in the region. While positive developments in the region have reinforced these expectations, some areas of concern remain. The indeterminate nature of peace talks, active cadres of anti-talk factions, poor implementation of ceasefire rules and persistent anti-foreigner sentiments have created unease and doubts. If these issues are not addressed in a timely and suitable manner, they can potentially damage the sustainability of fragile peace achieved in the region.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. See Rahul Karmakar, “Last NDFB faction in Assam calls truce”, The Hindu, January 17, 2020; and Prabin Kalita, “Guwahati: After 34 years of armed fight, NDFB finally disbands itself”, The Times of India, March 11, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 2. Bikash Singh, “644 cadres from eight insurgent groups lay down arms in Assam”, The Economic Times, January 23, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 3. Sadiq Naqvi, “Naga peace talks: Konyak faction joins working committee of political groups”, Hindustan Times, January 30, 2019. Also, see “Ceasefire with NSCN/NK, NSCN/R & NSCN/K-Khango extended for a year”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, April 15, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 4. “National Liberation Front of Twipra signs Memorandum of Settlement with govt”, The Economic Times, August 10, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 5. “Security Situation in the North Eastern States of India”, Two Hundred Thirteenth Report, Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs, Rajya Sabha, July 19, 2018, pp. 1-2.

- 6. “Status of Peace Process in the Northeast”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 7. Ibid. The NSCN (Khaplang) signed the ceasefire agreement in 2001 (which it unilaterally abrogated in 2015), NSCN (Khole-Kitovi) in 2012, and the NSCN (Reformation) in 2015.

- 8. “Understanding Naga conflict: How will the peace talks proceed?”, The Week, November 03, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 9. “Annual Report 2014-15”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2015, p. 15.

- 10. Rahul Karmakar, no. 1.

- 11. “Bodo Agreement – another success of PM’s vision of ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas’: Shri Amit Shah”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, January 27, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 12. Among the cadres, 836 were from NDFB (Progressive & Dhiren Bodo), 579 from NDFB (Ranjan Daimary) and 200 from NDFB (S). For details, see Hemanta Kumar Nath, “1,615 NDFB cadres lay down arms at surrender ceremony in Guwahati, deposit 178 weapons”, India Today, January 30, 2020 (June 02, 2020).

- 13. Prabin Kalita, no. 1.

- 14. Ministry of Home Affairs, no. 9.

- 15. Ministry of Home Affairs, no. 6.

- 16. K. Sarojkumar Sarma, “NNPGs, Kuki militant body sign peace pact”, The Times of India, January 20, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 17. “Tripura police arrests Ranjit Debbarma, ex-chief of outlawed outfit All Tripura Tiger Force, for sedition”, Firstpost, November 12, 2017 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 18. “Major Initiatives/Achievements of NE Division, MHA during 2019-2020 (upto 31.1.2020)”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 19. Rajeev Bhattacharya, “Why the Formation of a Common Platform by Insurgent Groups from the Northeast Should Give the Government Cause for Worry”, The Caravan, May 08, 2015 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 20. “Bhutanese govt promises to remove insurgents camps, but faces tough task”, India Today, April 14, 2003; “Bangladesh not to allow its territory to be used for anti-India activities”, Livemint, December 02, 2007; and “Will not allow our territory for any anti-India activity: Myanmar to India”, Zee News, August 22, 2016 (Accessed June 03, 2020).

- 21. “Royal Bhutan Army continue with its ‘Operation All Clear’ for ninth day”, Zee News, December 23, 2003 (Accessed June 03, 2020). Also, see Dipankar Banerjee and Bidhan S. Laishram, “Bhutan’s ‘Operation All Clear’: Implications for insurgency and security cooperation”, IPCS Issue Brief, No. 18, January 2004, pp. 1-4 (Accessed June 29, 2020).

- 22. “First time: Insurgent camps on Bangladesh soil reduced to zero, says BSF”, The Economic Times, New Delhi, July 14, 2018 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 23. “India, Myanmar conduct joint operation to destroy militant camps in Northeast”, The Hindu, June 16, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020); and Mayak Singh, “Anti-insurgency operations in Northeast lead to 2259 surrenders this year”, The New Indian Express, New Delhi, May 28, 2020 (Accessed June 03, 2020).

- 24. Ministry of Home Affairs, no. 18.

- 25. “Backdoor diplomacy yields results, Myanmar hands over 22 insurgents long-wanted by India”, The New Indian Express, Guwahati, May 15, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 26. The amount for an immediate grant to the surrenderee was revised from Rs. 1.5 lakhs to 4 lakhs and the monthly stipend from Rs. 3500 to Rs. 6000, besides offering incentives for surrendering weapons and ammunition. See “Annual Report 2018-19”, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2019, pp. 25-26.

- 27. Mayak Singh, no. 23.

- 28. Samir Kumar Das, “Conflict and Peace in India’s Northeast: The Role of Civil Society”, Policy Studies, No. 42, East West Center, Washington D.C., 2007, p. 43.

- 29. Arunabh Saikia, “The mothers of Nagaland are taking it upon themselves to keep the peace – yet again”, Scroll, November 19, 2019 (Accessed June 03, 2020). Also, see Soumyajit Patra and Samita Manna, “Integrative Reconciliation: Mothers in the Naga Movement”, Economic and Political Weekly, 43 (10), March 08-14, 2008, pp. 21-23.

- 30. Udayon Misra, “Assam: Peace Talks or the Fall of the Curtain on ULFA?”, Economic and Political Weekly, 46 (9), February 26-March 04, 2011, p. 10.

- 31. Reimeingam Marchang, “Out-migration from North Eastern Region to Cities: Unemployment, Employability and Job Aspiration”, Journal of Economic & Social Development, XIII (2), December 2017; and Duncan McDuie-Ra, “Beyond the ‘Exclusionary City’: North-east Migrants in Neo-liberal Delhi”, Urban Studies, 50 (8), June 2013, pp. 1625-1640.

- 32. As quoted in Duncan McDuie-Ra, “Beyond the ‘Exclusionary City’: North-east Migrants in Neo-liberal Delhi”, Urban Studies, 50 (8), June 2013, p. 1629.

- 33. “Historic framework agreement signed with government: NSCN-IM”, The Economic Times, August 03, 2015, New Delhi (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 34. “A clarification on the Naga settlement issue”, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, October 31, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 35. Anirban Roy, “Mysterious absence of Phungting Shimrang is ‘well oiled strategy’ of NSCN (IM)”, Northeast Now, January 23, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 36. Kunal Doley, “ST status to 6 Assam communities: Not everyone has tribal instinct”, EastMojo, February 18, 2019 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 37. Rajya Sabha, no. 5, pp. 7-8.

- 38. Vijaita Singh, “Armed gangs rule Nagaland: Governor”, The Hindu, June 25, 2020 (Accessed June 29, 2020).

- 39. R.N. Ravi, “Nagaland: Descent into Chaos”, The Hindu, January 23, 2014 (Accessed June 29, 2020).

- 40. Manas Roy, “Is NSCN (IM) running extortion racket under the garb of peace process?”, Northeast Now, September 07, 2018 (Accessed June 29, 2020).

- 41. Aung Maw, “Myanmar’s Return of Indian Rebels: Act of Friendship or Strategic Trade-Off?”, The Irrawaddy, May 18, 2020 (Accessed June 02, 2020).

- 42. Shishir Gupta, “Ulfa chief traced to China, but Beijing denies his presence”, Hindustan Times, February 02, 2014 (Accessed June 03, 2020).

- 43. S.K. Das, “’Ethnicity and the Rise of Religious Radicalism: The Security Scenario in Contemporary Northeastern India”, in S.P. Limaye, M. Malik and R.G. Wirsing (eds.), Religious Radicalism and Security in South Asia, Asia Pacific Centre for Security Studies, Honolulu, 2004, pp. 245-271. Also, see “Revenge link to rebel rise”, The Telegraph, September 11, 2015 (Accessed June 02, 2020).