The South China Sea Imbroglio

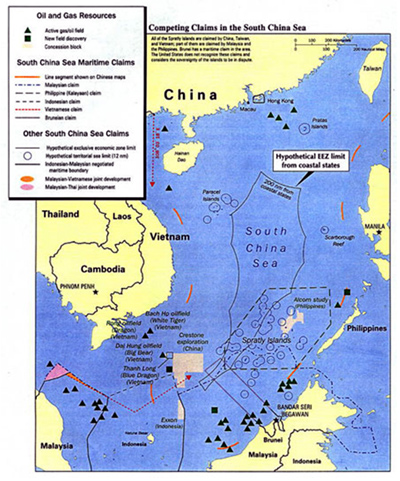

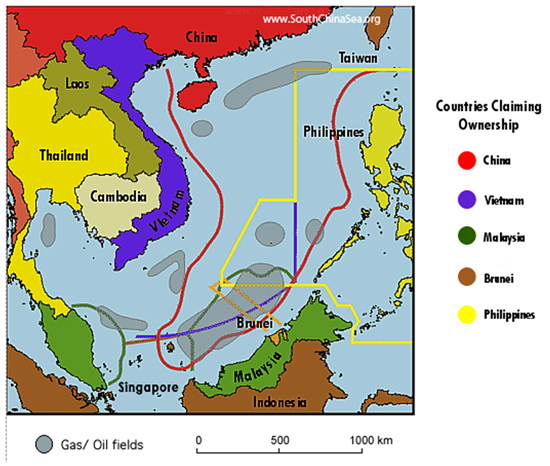

Competing claims over islands in the South China Sea and the sea area form the centre piece of the ongoing imbroglio. In addition China’s open statements to the US and India are making the security environment untenable.1 In the past some of the disputes led to military conflicts which remained small scale mainly due to the limited capacity of the nations involved. 2 An added factor to the ongoing territorial disputes is the availability of oil and gas in these waters. One Chinese estimate suggests potential oil resources as high as 213 billion barrels of oil (bbl). A 1993/1994 estimate by the US Geological Survey estimated the sum total of discovered reserves and undiscovered resources in the offshore basins at 28 billion bbl. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) the real wealth of the area may well be natural gas reserves.3 As per estimates the area holds about 900 trillion cubic ft (25 trillion cubic m) of gas reserves. The combination of these two factors complicates the issue further as the claims over the islands include adjacent waters that have been interpreted as per UNCLOS by the competing nations so as to gain access to the oil and gas rich areas (see map below). The Spratly Islands alone consist of about 170 plus land features that are spread over a sea area of about 240,000 square kilometres. Of these only 36 are islands at high tide and have a total land area of about eight square kilometres. China has so far confiscated 12 geographical features in the Spratlys, Taiwan one, Vietnam 25, the Philippines eight, and Malaysia five.4 This aspect is likely to stall all hopes of any bilateral or multilateral resolution of the territorial disputes. These territorial disputes, which were hitherto a sovereignty issue, have now grown to encompass a race for natural resources, thus adding another complex dimension to the imbroglio.

Competing claims over islands in the South China Sea and the sea area form the centre piece of the ongoing imbroglio. In addition China’s open statements to the US and India are making the security environment untenable.1 In the past some of the disputes led to military conflicts which remained small scale mainly due to the limited capacity of the nations involved. 2 An added factor to the ongoing territorial disputes is the availability of oil and gas in these waters. One Chinese estimate suggests potential oil resources as high as 213 billion barrels of oil (bbl). A 1993/1994 estimate by the US Geological Survey estimated the sum total of discovered reserves and undiscovered resources in the offshore basins at 28 billion bbl. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) the real wealth of the area may well be natural gas reserves.3 As per estimates the area holds about 900 trillion cubic ft (25 trillion cubic m) of gas reserves. The combination of these two factors complicates the issue further as the claims over the islands include adjacent waters that have been interpreted as per UNCLOS by the competing nations so as to gain access to the oil and gas rich areas (see map below). The Spratly Islands alone consist of about 170 plus land features that are spread over a sea area of about 240,000 square kilometres. Of these only 36 are islands at high tide and have a total land area of about eight square kilometres. China has so far confiscated 12 geographical features in the Spratlys, Taiwan one, Vietnam 25, the Philippines eight, and Malaysia five.4 This aspect is likely to stall all hopes of any bilateral or multilateral resolution of the territorial disputes. These territorial disputes, which were hitherto a sovereignty issue, have now grown to encompass a race for natural resources, thus adding another complex dimension to the imbroglio.

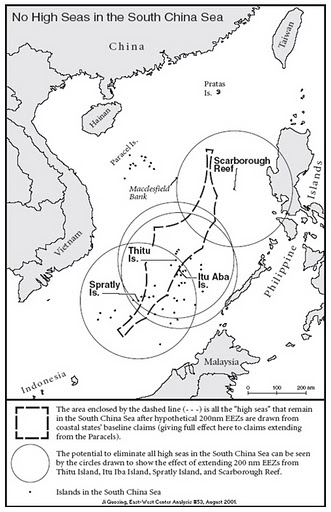

An attendant issue with the territorial claims is their effect on the high seas area. Legitimacy given to any of the claims over the islands would effectively eliminate the high seas area (see map below) thereby diluting the US and Indian stance on freedom of navigation, erasing the global commons in the region from the map and abrogating UNCLOS both in letter and spirit. Therefore, it is in China’s interest that the present instability be maintained in order to permit continued bilateral engagements as it tilts the balance in its favour vis-à-vis its weaker maritime neighbours. China continues to rebuff any internationalisation of the issue and has from time to time issued statements backed by subtle actions and strong arm tactics in order to deter any power play by both intra- and extra- regional nations.

On 16 September 2011, the Xinhua news agency issued a statement on the visit of the Indian External Affairs Minister to Hanoi where he co-chaired the 14th India-Vietnam Joint Commission meeting (JCM) relating to the ongoing Indo-Vietnamese oil exploration in the blocks in which ONGC has a stake. It stated:

“China has warned Indian companies to stay away from the South China Sea, as aggressive overseas explorations from Indian side in the highly sensitive sea, over which China enjoys indisputable sovereignty, might poison its relationship with China, which has been volatile and at times strained. “

The last lines of the statement could actually be viewed as a warning:

“It is wise for those trying to feel out China’s bottom line to wake up to the reality that China will never yield an inch in its sovereignty and territorial integrity to any power or pressure. On this basis, the Indian government should keep cool-headed and refrain from making a move that saves a little only to lose a lot. “5

This has added a new dimension to the ongoing turmoil in the South China Sea. The Chinese have vehemently protested India’s ‘ingress’ into their core area of interest and what they claim as their waters. The options for India to extend its economic and maritime interests in the South China Sea in the face of Chinese opposition are fast closing. A strong Indian signal to China should be the first step. The South China Sea has a number of nations that India is engaging economically and diplomatically. As India grows and its influence expands the number and intensity of such engagements will and should increase. This stance should not be hindered by the view point of China since these engagements are based on accepted international laws and do not in any way lend a bias to the ongoing maritime disputes as these disputes are to be resolved by the nations involved.

India’s relations and ongoing engagements with the nations in South China Sea except China are based on strategic, economic and maritime interests and can therefore be strengthened on these lines. In contrast, India’s relationship with China has been one of mistrust and suspicion due to the land border issue and China’s linkages with Pakistan. China’s infrastructure build up especially in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir is being watched closely by India. This will be an impediment to the forging of an understanding between India and China and it could also subtend the ongoing Indian engagements in the South China Sea and oil exploration progress achieved so far. In so far as India’s ‘ingress’ is concerned, “China’s protest blatantly disregards its own policies in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir,”6 therefore this is a card that could be played when engaging China and would require a stronger stance, stronger signalling, and a bolder policy. However, if this is not considered viable then another option would be to delink the maritime issue from the border issue and continue pursuing the ‘Look East Policy’ in the maritime and oil exploration domain. In either case it would entail India respecting the claims and sensitivities of the other nations in the area while engaging with them.

- 1. The statement by the Xinhua news agency on 16 September 2011 (covered subsequently in the text) and the Chinese Foreign Ministry categorising Hillary Clinton’s July 2010 call for a binding code of conduct in the South China Sea as an attack on China are two examples.

- 2. In 1971 the Philippines attempted to occupy Itu Aba, which was under Taiwan’s control, but were repulsed. The Philippines have also had a few minor skirmishes with Chinese, Vietnamese and Malaysian forces. In 1974 the Chinese seized the Paracels from Vietnam killing several Vietnamese troops. In March 1988 China and Vietnam clashed in the Spratly Islands in what is called the ‘Battle of Fiery Cross Reef’. Around 75 Vietnamese were killed or missing and three Vietnamese ships were hit.

- 3. See http://www.eia.gov/countries/regions-topics.cfm?fips=SCS. Accessed on 10 October 2011.

- 4. Robert D. Kaplan, “The South China Sea is the Future of Conflict”, Foreign Policy, Sep/Oct 2011, p. 4.

- 5. See http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/indepth/2011-09/16/c_131142806.htm. Accessed on 10 October 2011.

- 6. Kanwal Sibal, “China Stance in East Asia at Odds with POK Policy”, India Today 11 October 2011.