Total Recount in Afghanistan: What Next?

- July 26, 2014 |

- Issue Brief

As per the compromise agreement worked out by the US Secretary of State John Kerry on July 12, both the leading Afghan presidential candidates, Dr. Abdullah and Dr. Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, have agreed to a fresh and total audit and recount of “every single ballot,” about 8.1 million, cast in the June 14 run-off election. Kerry’s diplomacy for now has partly succeeded in averting a major political crisis by addressing the key technical issue of auditing and recounting of votes and collation of final results in a transparent manner under wider international supervision. However, his proposal that the two presidential contenders, irrespective of the final outcome of the run-off vote, must come together to form a “national unity government” and subsequently work towards changing the political system of the country, might open up several larger issues which are bound to have huge social, political and security implications for Afghanistan and the region.

There is a lot of ambiguity in the Kerry-brokered agreement, the text of which is still not available for public scrutiny, and both Abdullah and Ghani are interpreting its various aspects in their own ways. Perhaps, the agreement leaves a lot of room for speculation, leading the two leaders and their sympathisers to draw their own inferences keeping in view their interests in the emerging scenario. While the UN and Afghan election officials in Kabul struggle to make the two contending group of election observers agree on a standard auditing criteria for validation-invalidation of votes, it is important to understand the shifting or the evolving socio-political equations within the country. Basically, what changed between April 05, when the first round of voting was held, and the June 14 run-off election.

Complete Reversal

Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani, who emerged as top two contenders from among the eight all-Pashtun presidential candidates from the first round of vote, had to go for the second round of vote or the run off election on June 14 as neither had secured absolute majority or the mandatory 50 per cent vote required to win the election. As per the final results of the first round of vote held earlier in April, Abdullah had emerged as the leading candidate securing 45 per cent votes, a solid 13 per cent lead over Ashraf Ghani, who came second with 31.56 per cent votes. The preliminary result of the June 14 run-off election, which was declared on July 07, was a complete reversal of the outcome of the first round of vote: this time it was Abdullah who had lost to Ashraf Ghani and by almost the same margin. Ghani had secured 56.44 per cent votes while Abdullah trailed behind at 43.56 per cent votes.

In quite a contrast to the first round of vote held in April, the second round of vote was marred with reports of massive rigging of votes in parts of the country and the partisan role of the election commission, from ground officials to the secretariat in Kabul. Within hours of the run-off election, Ashraf Ghani was being projected as the final winner. Abdullah, who has throughout been sceptical of the role of the government-appointed members of two key electoral bodies – the Independent Election Commission (IEC) and the Independent Electoral Complaints Commission (IECC) – and especially that of the incumbent President Hamid Karzai and his close aides in influencing the outcome of the electoral exercise, was quick to boycott the whole process and call for international intervention. Soon audio tapes alleging the direct involvement of the head of the IEC Secretariat, Zia-ul Haq Amarkhel, in rigging of votes reportedly in favour of Ashraf Ghani appeared, and he had to subsequently resign. There were reports of stuffing of ballot papers at several polling booths, often facilitated by the local election staff and biased administrative machinery. At many places, particularly in the east and north, the total number of votes cast far outnumbered the registered voters in the area. The IEC had to later acknowledge that several irregularities were noted in the conduct of the second round of vote on June 14.

It is noteworthy that after the first round of vote in April, of the total 121 complaints filed by the presidential candidates, 115 were filed by Abdullah alone, four by Ashraf Ghani, one by Zalmai Rassoul and one by Daoud Sultanzoy. Later, as it became clear that their will be a run-off, while Ashraf Ghani further toned down his criticism of the election commission, Abdullah grew further suspicious of their commitment to fair elections.

Immediately after the June 14 run-off election, Abdullah openly accused the election commission of working in collusion with the presidential palace to manipulate the entire electoral exercise in favour of his rival Ashraf Ghani. He pulled out all his observers from the election commission and refused to further participate in the process. His supporters meanwhile declared him as the winner and threatened to form a “parallel government” if the election commission failed to address their several concerns regarding the conduct of the run-off election. Both the US and the UN mission in the country swung into action to convince Abdullah to rejoin the electoral process which he did after direct American mediation.

What has been missed out in this whole commotion is the larger fact that apart from rigging of elections, as also evident from reports that over a million votes may simply be invalidated, a quite shift in voting pattern too had taken place in parts of the country. The key question here is whether it was just about consolidation-division of votes along ethnic lines, or is it that today’s Afghan polity is struggling to respond to the old and familiar challenges in a different manner, as evident from the high voter turnout and cross-ethnic nature of the alliances attempted by both the candidates, particularly Ashraf Ghani? The likely answer is perhaps both.

Shift in Voting Pattern

The shift in voting pattern particularly in Pashtun-dominated provinces was obvious in the run-off election as the contest had narrowed down to two top contenders. Earlier, in the first round of election, the Pashtun votes were divided and scattered among various other candidates, all of whom were Pashtuns, including Abdullah, who is born of a Pashtun father and a Tajik mother. It is quite another thing that Abdullah is regarded more as a Tajik than Pashtun because of his longstanding association with the Tajik leadership in the north.

First Round of Vote

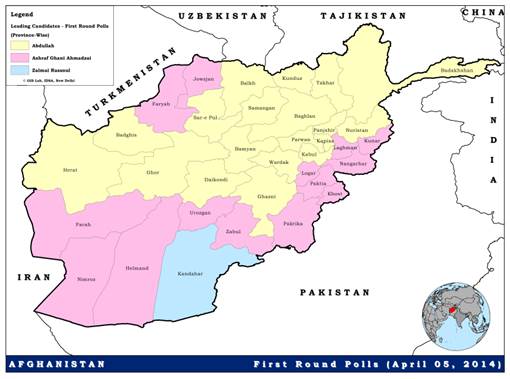

According to the final result of the first round of voting held on April 05, of the total 34 provinces in the country, Abdullah was the first leading candidate in 19 and second leading candidate in six provinces. Ashraf Ghani was the first leading candidate in 14 and the second leading candidate in 10 provinces. Zalmai Rassoul, who ended on third position, had emerged as the leading candidate only in the southern Kandahar Province (see Map 1 below).

Map 1: Leading Presidential Candidates (Province-Wise): As per the Final Result of the First Round of Voting Held on April 05, 2014

Second Round of Vote

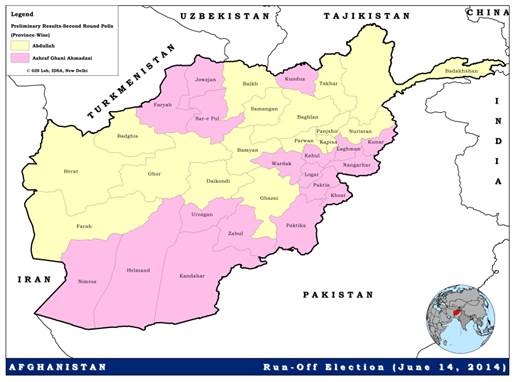

As per the preliminary count of the run-off election held on June 14, Abdullah emerged as the first leading candidate in 16 provinces, down from 19 in the first round of vote. On the other hand, Ashraf Ghani secured the highest number of vote in 18 provinces, up from 14 in the first round of vote. While Ghani replaced Abdullah as the leading candidate in the northern provinces of Kunduz and Sar-e Pul and in the central provinces of Wardak and Kabul, Abdullah could replace Ghani as the leading candidate only in the western Farah Province (see Map 2 below).

Map 2: Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai as Leading Candidates (Province-Wise): As per the Preliminary Results of the Run-Off Election Held on June 14, 2014

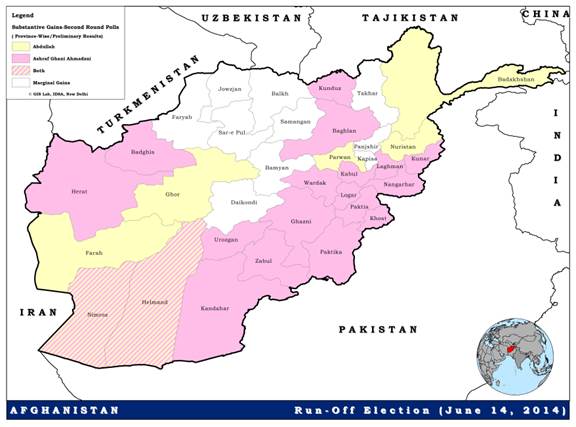

Apart from gaining lead over Ghani in Farah Province, Abdullah made substantive gains mainly in areas where he had secured the maximum number of votes earlier in the first round of elections, for instance in the northern province of Badakhshan, in the central provinces of Ghor, Parwan, in the eastern province of Nuristan, and in the southern Nimroz and Helmand Province. This basically means that despite support from other leading presidential candidates particularly former Foreign Minister Zalmai Rassoul, who had secured the highest number of votes in the southern Kandahar Province in the first round of voting and was initially seen as Karzai’s favourite; former Governor of Nangarhar and Kandahar Province, Gul Agha Sherzai, who had secured the second highest number of votes in Kandahar Province; and the veteran Islamist leader Abdul Rab Rassoul Sayyaf, Abdullah could not make further inroads into the Pashtun-dominated provinces in the south and east. It was clear that their supporters did not go along with them to vote for Abdullah in the run-off election and instead voted in favour of Ashraf Ghani.

Unlike Abdullah, Ghani benefited in a big way from the consolidation of Pashtun votes in the south and east and even in the northern province of Kunduz which has pockets of strong Pashtun presence. Even in provinces where he was the second leading candidate in the first round and still is in some of them, his voting percentage registered a moderate to often a notable increase. A cursory glance through the preliminary results of the run-off election suggests that Abdullah substantively improved his tally of votes mainly in 07 provinces listed before, whereas Ghani made substantive gains in nearly 19 provinces mainly in the south and east and in some western parts of the country (see Map 3 below).

Map 3: Substantive Gains Made by Abdullah & Ashraf Ghani (Province-Wise): As per the Preliminary Results of the Run-Off Election

Though both the candidates gained in other provinces as well, but the increase in their share of votes in these provinces was comparatively marginal. In the northern Takhar Province, Abdullah retained his lead by a narrow margin. Similarly, despite making substantive gains in Kabul, Ashraf Ghani won Kabul from Abdullah only by a small margin. In another instance, as shown in the above map, though Ashraf Ghani emerged as the leading candidate in the southern Nimroz and Helmand Province, both the candidates had made substantive gains in terms of their respective share of votes in the two provinces compared to the first round of elections.

Abdullah’s vote share had clearly reached its limits as he could not have made substantive gains in the ethnically-mixed and Pashtun-dominated provinces of the country where he is seen as more of a Tajik leader than one with mixed Pashtun-Tajik ancestry, whereas in case of Ghani, a full Pashtun, there was enough space and scope to further consolidate and widen his support among his co-ethnic Pashtun communities.

Emerging Alliance and Divide

Within hours of Kerry’s departure from Kabul, the Abdullah group and the Ashraf Ghani group began sparring over the nuances of the term “national unity government.” For Abdullah and his followers it was initially about forming a ‘coalition,’ while for Ashraf Ghani, it was not about coalition but ‘sharing of power.’ Later, the two decided to avoid usage of terms such as ‘deal’ and ‘coalition’ which have come to have negative connotations in the Afghan polity based on the past experiences where every coalition based on deals struck among factions with conflicting interests was invariably superseded by violent struggle for political supremacy.

Both Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani are yet to agree on the mechanism for sharing power. According to the Afghan media reports, it was initially stated by the Abdullah group that the winning side would appoint the losing candidate or his nominee as the chief executive, while the Ghani camp insisted that the chief executive would be appointed by the winning candidate and that the losing candidate or his nominee would be appointed as the head of the opposition and that the two would mutually decide on the allotment of cabinet and other positions. This could become a major issue of conflict between the two sides both before and after the formation of the national unity government. Perhaps, both the candidates would be in a better position to decide on how to share power after the final results of the run-off election are released in August. It is also too early to say whether the two candidates would actually be able to form a national unity government. In such a scenario, another round of international mediation might be required.

Meanwhile, to further strengthen his position, Ashraf Ghani has announced that if he wins the run-off election, Ahmad Zia Massoud, former vice president and brother of former Tajik commander Ahmad Shah Massoud, would be his chief executive, to be appointed as prime minister after two years once necessary amendments to the constitution are made. It was stated that the president would be the head of the state and prime minister would be the head of the government. This might further complicate the interpretation of the provisions of the Kerry-brokered agreement to introduce a much more inclusive and a broad-based power-sharing arrangement.

Ashraf Ghani’s candidacy today represents a tenuous Pashtun-Uzbek alliance. Realising the need to further strengthen and widen his support base, he is trying to divide or make inroads into the Tajik constituency, the Karzai-style, by putting forward Ahmad Zia Massoud’s name as his future prime ministerial candidate. However, there might be differences within the Ghani camp on the issue of nominating Massoud. Abdullah, on the other hand, has successfully crafted a strong Tajik-Hazara alliance but has failed to make inroads among the Pashtuns despite having Muhammad Khan, a Pashtun and a former member of Hezb-e Islami, as his vice presidential co-nominee. The emergence of a loose Pashtun-Uzbek and strong Tajik-Hazara pre-election coalition has the potential to turn into a major socio-political fault line after 2014 if the two candidates failed to forge a national unity government. The politics in the run up to the formation of the next coalition anyway is bound to be a highly competitive, complicated and therefore a protracted exercise. It remains to be seen if Kerry’s proposal to change the political system would create new rifts and destabilise the country or lead to the establishment of a sustainable balance of power within the country.

Much More to Kerry’s Diplomacy

The emphasis in the Kerry-brokered agreement first on the formation of a national unity government and thereafter on changing the political system of the country from a highly centralised presidential system to a more decentralised parliamentary system of government with a provision for the post of a prime minister, is no “miracle” as described by the UN special envoy Jan Kubis. Based on the experience of the 2009 presidential election in which too Kerry had to mediate between Karzai and Abdullah on the issue of run-off election, and more recently the political crisis in Iraq, both the UN mission and the American establishment had reasons to be sceptical about the viability of a centralised political set up in post-Karzai and post-ISAF Afghanistan. The political deadlock between Abdullah and the country’s election commission simply opened up an opportunity for the UN and the US to restructure the political system of the country in view of the existing and emerging divide within the Afghan polity. It could also be seen as an acknowledgement of the changed socio-political landscape of the country where neither Pashtun elites nor the mélange of minority ethnic factions could be the sole arbiters of power. The proposed change in political system, however, would have huge implications for the ongoing institution-building process in the country as it would redefine the centre-province as well as the inter-ethnic relations.

The idea of diluting the powers of the president could not have gone down well with President Karzai and a large section of Pashtun elites. The long-held distrust between Pashtuns and the non-Pashtuns as well as among the various ethnic factions in the north could prove to be a major stumbling block, whether it is about forming a unity government or initiating the process of constitutional amendment after 2016. It is an irony of history that today Americans are pushing for a national unity government in Afghanistan, something they had refused to endorse and support in the same country nearly two decades ago. After the retreat of the Soviet forces in 1988-89, the then Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah’s effort to forge a national unity government had failed despite repeated appeal for support from the US and its various Cold War allies in the region including Pakistan.

Similarly, in another twist of history, Kerry’s proposal advocated creating the post of prime minister by changing the constitution, something which both President Karzai and the US had vehemently opposed and out rightly rejected exactly a decade ago. When the new constitution was being drafted in 2003, the minority ethnic factions had favoured the idea of creating the post of a prime minister to avoid undue concentration of power with the president. But the provision for the post of prime minister was taken out of the draft before it was placed for debate and ratification before the 502-member Constitutional Loya Jirga specially convened for the purpose. The Jirga, which started on December 14, 2003, and was initially slated to be over in 10 days, went on for 22 days until the draft constitution was finally approved and ratified with 40 amendments on January 04, 2004.

As argued in one of my earlier articles, Politics in Post-Taliban Afghanistan: An Assessment (Strategic Analysis, 2005), the debate that went into the making of new constitution “provided a broad sweep of divergent notions about state system and distribution of power in the backdrop of prevalent identity-based power politics.” The adoption of a highly centralised presidential form of government was to an extent in contradiction to the spirit and provisions of the Bonn Agreement which had called for the “establishment of a broad-based, gender-sensitive, multi-ethnic and fully representative government.” However, drafting of the new Constitution could still be regarded as the first major step towards national reconciliation as it duly acknowledged the multiple identities that define the Afghan nation.

Interestingly, even as Afghanistan experimented with various political systems, from monarchy to centralised presidential forms of government in 1970s and 80s to several coalitions among various anti-Soviet resistance factions during 1992-96, the post of prime minister has always been part of it. Thus, neither the idea of a national unity government or a centralised presidential form of government, nor the idea of a prime ministerial set up, is new to Afghanistan. Given the dismal track record of various past transitions, Afghans in general are likely to remain as sceptical of the change in political system as ever before. However, in the current scenario, a successful political transition in 2014 is critical to building the momentum for transforming the political system of the country after 2016.

Taliban Stakes

Though Taliban remain vehemently opposed to the post-2001 political process and have resisted all offers of political reconciliation with Kabul, it is difficult to conclude that Taliban simply have had no stakes in the election process. They may not have carried out large scale attacks on April 05 when the first round of voting had taken place, but that was no affirmation of Taliban giving up on their sustained campaign against the Afghan Government and the retreating Western forces. Terming the election process as “un-Islamic” and “deceitful drama,” the statement issued by the ‘Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’ on June 02 had called for complete independence from the Western occupation and the restoration of the Islamic system in the country, which “can be achieved neither by elections, selections, coalitions nor following alien policies” but by making “huge sacrifices.” As is the case every year, Taliban did announce their summer offensive this year too and have since carried out series of spectacular attacks in the heart of the capital city in the weeks preceding and following the April vote. There were also reports of Taliban chopping off the fingers of 11 voters in the western Herat Province.

The very fact that all eight presidential candidates were Pashtuns and, more importantly, since all of them had openly endorsed the long-term Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) with Washington, Taliban leadership must have closely followed the election process. Taliban in their statements often refer to the BSA as “enslavement” or “occupation” agreement with the invaders. In their statement issued on June 24, while referring to the election process as “an illusory drama of the Westerners and their puppets,” Taliban had berated all the presidential candidates for “pledging the prolongation of occupation and the existence of foreign invaders” by endorsing the BSA.

The emergence of Abdullah, who was a key member of the anti-Taliban Afghan coalition in the 1990s, as the leading presidential contender must have further caught the attention and aroused the interest of the Taliban leadership in the final outcome of the election. Though it is difficult to verify whether the Taliban had any role in mobilising support in favour of Ashraf Ghani, but in the Taliban evaluation Abdullah’s alliance with Hazaras certainly represented a more compact and formidable force compared to Ashraf Ghani’s alliance with Uzbek Commander Abdul Rashid Dostum. In the Taliban perception, Abdullah could be seen as better positioned to create a much stronger centre in Kabul and offer much effective opposition to them. The Haqqani-Taliban network would therefore prefer to see Ashraf Ghani as the winner for he still does not enjoy any mass support base among the Afghan people and his tactical alliance with Dostum in unlikely to evolve into a strong political alternative.

Kerry’s idea of first establishing a national unity government and subsequently changing the political system, which would ensure wider distribution of power at the centre as well as dissemination of authority at the sub national levels, could not have gone down well with the Haqqani-Taliban leadership too. It remains to be seen whether the formation of a national unity government and the process for transforming the political system of the country would emerge as a major challenge or provide a greater opportunity for the Haqqani-Taliban network to exploit to their advantage the persisting divide between the Abdullah-led and the Ashraf Ghani-led alliance.

2016, the next 2014

The year 2016 is clearly emerging as another watershed in the making in the decades-old Afghan conflict. As per the compromise brought out by Kerry, necessary amendments to the Afghan Constitution should be made in 2016 to transform the political system of the country. A Loya Jirga would have to be convened by the next president in Kabul to discuss and build necessary consensus for the proposed changes in the political system of the country. The process of constitutional amendment can only be initiated after the new parliament is formed as parliamentary elections are due in 2015.

However, building national consensus on various aspects of the new political system would be a complicated exercise in view of the divergent perceptions about state system prevalent among different communities and political formations in the country. It is clear that international engagement would remain a critical component, rather an essential pre-requisite, to sustaining the next stage of political transition in Afghanistan. The role played by the UN mission in Afghanistan and the timely American mediation has once again brought out the fragility of the post-Taliban political system and, more importantly, has exposed the continuing inability of the Afghan institutions to cope with pressures of transition without external support.

If the incumbent president’s office and the electoral institutions of the country had managed to diffuse the crisis in a timely and convincing manner, the trust and confidence of the Afghan people which is very critical to widening as well as institutionalising the social and political space for an inclusive political order would have acted as the biggest deterrence to the Haqqani-Taliban network in the coming years. As stated in my earlier comment, For Now, it is Ballot over Bullet in Afghanistan (April 2014), this election process is about building a political order which is in tune with the changing socio-political realities and is mindful of the several challenges ahead, the most important being how to keep the international community engaged.

Earlier, in May 2014, President Barack Obama had announced that about 10,000 American troops would stay in Afghanistan until 2016. Obama’s second and final term of presidency too would come to an end in early 2017 and perhaps it will be for the next American president to decide on the nature and scale of future engagement or disengagement from Afghanistan. Though the BSA might be signed as soon as the next Afghan president is appointed, the Obama Administration may not be keen on further enhancing the American commitment until the national unity government is formed and begins to deliver results and the process of constitutional amendment is successfully put on track.

Both these developments mean that the ongoing security and political transition in the country will not end in 2014. In fact, Afghanistan is likely to enter into a new phase of transition beginning in 2016 and which is likely to continue for several more years to come. In the current circumstances, emergence of a clear cut winner from the run-off election and the formation of a sustainable national unity government are critical to the success of the future political process. As all the votes cast in the run-off election are audited and recounted under international supervision, the final outcome could be a close finish with winning candidate leading by a much narrow margin.

The Kerry-brokered agreement might increasingly come in for criticism in the coming months for lacking in clarity on various aspects of the proposed national unity government. But, at the same time, it might be surmised that ambiguities in Kerry’s proposal provides enough space and political flexibility for the Afghan leadership to interpret and decide on the nitty-gritty of sharing power as per the post-election scenario, and later build necessary consensus within the country to initiate the process of constitutional amendment in a legitimate manner. This would be critical to establishing the whole process as one that is “Afghan-led” and “Afghan-managed.” Perhaps, only time will tell whether Kerry’s diplomacy has ushered the country into what is supposed to be the “Decade of Transformation” (2015-2024) or it has simply opened up a Pandora’s Box leading to unmanageable chaos and anarchy in the coming years.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.